Starting off our Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles review – it’s worth noting the game was developed by Luminawesome Games, a 4-person indie game studio from Canada. After winning an Unreal Game Jam in 2014 and receiving funding from Creative BC in 2017, their initial prototype game Bump was expanded into a full-length puzzle platformer adventure built in a new engine and published by Wired Productions this year.

Check out our Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles review to learn more about this fascinating puzzle game and find out whether it’s worth your time!

Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles

Developer: Luminawesome Games

Publisher: Wired Productions

Platforms: PC, Playstation 4, Xbox One, Xbox Series S/X, Nintendo Switch

Release Date: February 20, 2020 (Steam), April 21, 2022 (Everywhere Else)

Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles begins as soon as you pick up the controller, with no intro cutscene or exposition. In fact, there’s no explicit worldbuilding to speak of; the visuals and mechanics do all the heavy lifting to set the tone for this experience. I vastly prefer this method of storytelling. Despite being more opaque than a standard AAA video game story full of narration, audiologs, and codex entries, there’s still a feeling of gravitas behind your actions in this game.

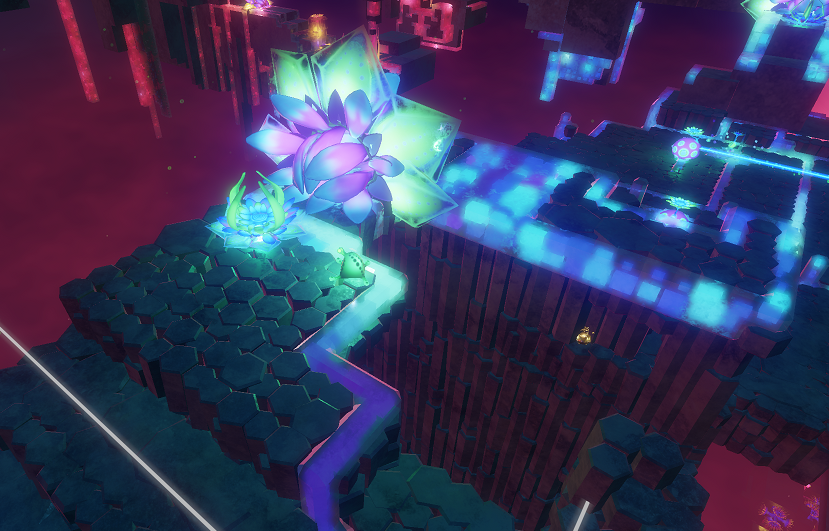

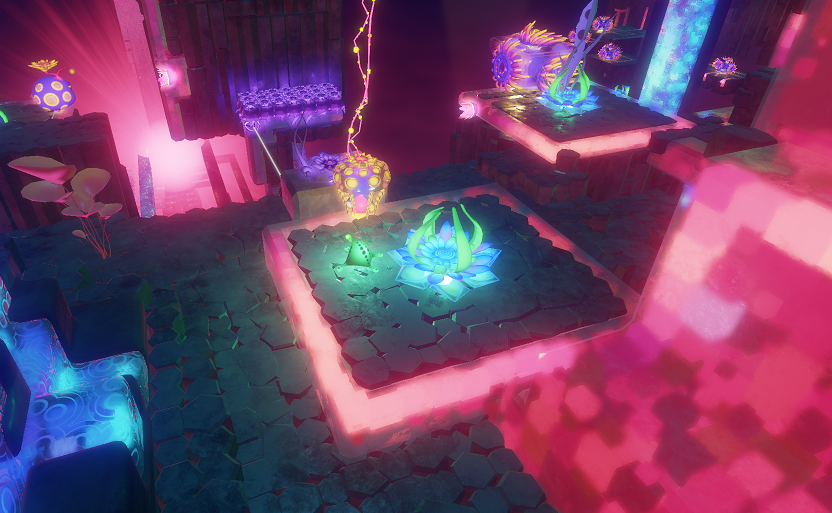

You play as Lumote, a blue amoeba-like creature living in a dark void reminiscent of the deep sea. Lumote has the ability to change the color of his environment and manipulate the other creatures that inhabit it, which closely resemble sea creatures like anemones, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. This allows the player to solve puzzles in order to navigate a series of interconnected narrow platforms toward a central hub, which is occupied by the Mastermote.

This game runs on an original 3D engine called rEngine. It’s impressive how well it performs— for my Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles review, I played on an Xbox Series X, although there’s also a Switch port that maintains a stable framerate.

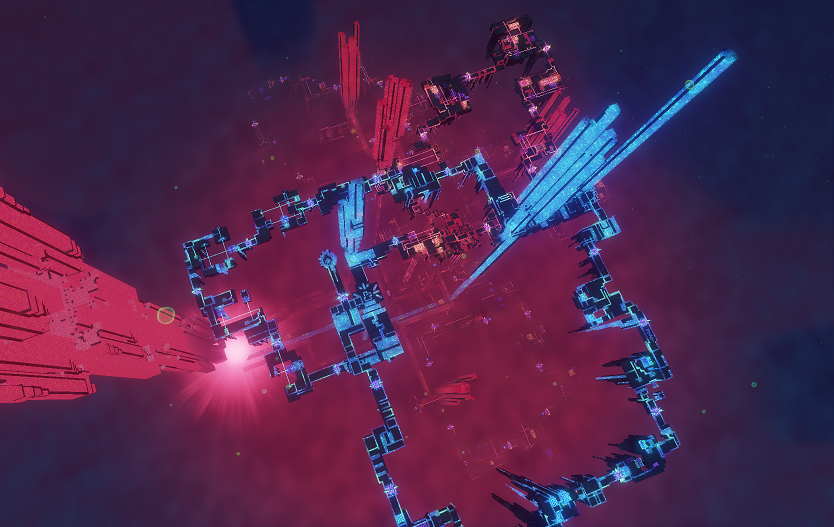

What’s even more impressive about this game engine is how the structure of each world means that there are no load gates in between each puzzle. You can walk from the beginning to the end in one shot, and there’s even an achievement if you pull this off without dying.

Tons of bright neon lights color the game environment, which change from red to blue as you solve puzzles to progress further in the game. At the same time, cute sound effects indicate objects you can interact with, and a pleasing little chime can be heard when you complete each puzzle.

Some of these noises are more endearing than others— towards the end of the game, I was getting pretty sick of the train whistle noise when moving around a laser emitter. Additionally, I had to take frequent breaks after about 30 minutes to an hour of playing due to eye strain from all the bright colors. When checking the accessibility features in the options menu, there’s no way to lessen the intensity of the lighting, although this may be different on the PC version.

Overall, this aesthetic reminds me of similar indie games made by Nicklas Nygren aka Nifflas, such as Uurnog and Knytt Underground. That isn’t to say that this game’s setting is unoriginal – I can say with full confidence that this is the first undersea puzzle platformer starring an amoeba I’ve ever played.

After spending about 20 minutes on the tutorial, moving a larger block into a receptacle triggers a large… event of some kind, punctuated by a music sting. The camera pulls away to show a much larger network of paths with puzzles to solve. Although not as impressive as the infinite recursive design of Manifold Garden, this is still an impressive moment that demonstrates the power of Lumote’s game engine.

You only need to use two buttons on the controller for the entirety of Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles: one for jumping, and one for interacting with objects. By “taking control” with the B button, you stand still and emit light, which can have different effects on different objects. Some platforms will extend or retract, while other objects will allow you to move them to different locations. It sounds simple, but the ways you can use this single input become very complex.

After a few hours of warm-up puzzles, levels become noticeably more difficult with moving platforms, lasers, and positive/negative currents. Learning the “language” of this game’s puzzles by connecting colors to functions is part of the challenge; it really scratches a puzzle solving itch in my brain similar to the way I felt when playing The Witness. To illustrate what I mean, let me walk you through the solution to puzzle W1-T4-8.

I had to use one of two movable blocks to block a laser, which changed a blue jellyfish red. This allowed me to lower a platform in order to move the second block to one switch. Then, I used the red jellyfish to move the blue jellyfish across a gap by powering a red-powered moving platform, which allowed me to place the blue jellyfish on a second switch. This turned the moving platform from red to blue, which allowed me to manipulate it manually, so I could guide the red jellyfish back along the moving platform across the gap and around the corner where the first switch was.

This was the location of a second red-powered moving platform, which I powered with the red jellyfish to cross an even larger gap. Then I placed the red jellyfish on the third switch and made a tricky double jump to clear the shorter gap without the aid of a moving platform. I say this jump is tricky because I failed it several times, which caused the entire level to reset from the beginning. But once I made the jump, then I could move the first block away from the laser and turn the red jellyfish blue, triggering the third switch from a distance and completing the challenge.

Figuring out the correct path to take took a lot of trial and error, as did the platforming. But at the end, I felt satisfied and almost as though I was getting away with something. Why was there a second block left over? Maybe that jump at the end was so difficult because I wasn’t supposed to solve the level that way; did the developers intend on that solution?

For a brief moment, the line between intended chain of events and emergent, lateral thinking style of problem solving was blurred, which is extremely rare when I play puzzle games.

In my experience, the solution to a puzzle in a game seems obvious in retrospect. Typically, you can clearly see how the designer had an intended solution in mind from the beginning and worked their way backward from there. Perhaps it’s because of the lack of dialogue, or hints, or virtually any language whatsoever, but I didn’t feel that way after finishing this puzzle. To me, this ambiguity feels like a resounding success in puzzle design.

After the third tower, a “Hub” level is unlocked with the appearance of branching paths, including a teleporter to the next 3 “towers” in lieu of the standard gated path progression. This allows you to complete the next levels in non sequential order, presumably a way of taking breaks from one level to try another set. It’s a nice feature to prevent frustration when stuck on one puzzle, but the inability to backtrack to previous puzzles after their completion is a minor nuisance.

Some puzzles feel like that old riddle where you have to figure out how to get the knight, the maiden, and the thief across the river in a small canoe. Other puzzles feel like you’re trying to connect a circuit on a breadboard— for all you zoomers, that’s like a physical version of redstone circuitry we used to have to do in middle school after dissecting the frog.

Here’s the biggest complaint I have in my Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles review. It would be nice to be able to fast forward in order to decrease the wait time for moving blocks; after The Talos Principle introduced me to this feature, I lost all patience for slow moving blocks in any other puzzle game.

One puzzle required me to wait several extra minutes after figuring out the solution just for all the molasses-paced moving platforms to properly orient. There’s also a noticeable delay when manually manipulating the anemone and nudibranch platforms that can further frustrate timing.

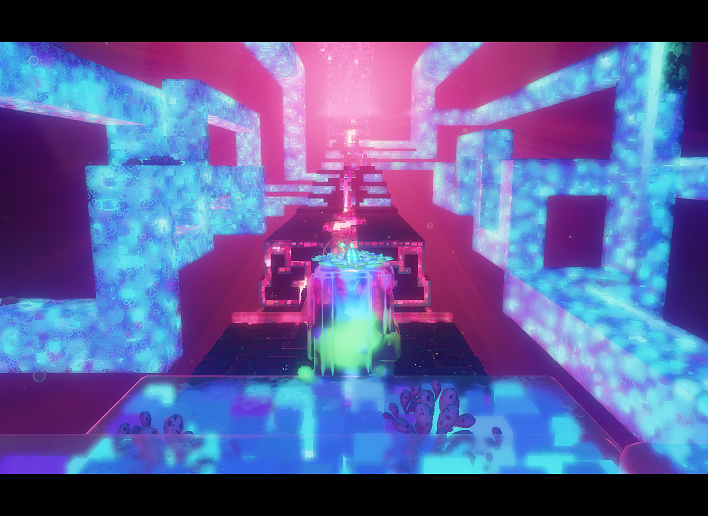

Here’s another gripe I have with Lumote. Tower 5’s gimmick involves moving little sea creatures that direct light energy as lasers. These levels were the most frustrating for me because the rules for what they can do felt too abstract for the minimalist explanations provided by the game.

Sometimes, placing these laser emitters on a lit track would cause the opposite color to appear instead— presumably based on the “flow” of energy interrupting a circuit. Other times, placing the block would remove color entirely and disconnect the circuit. This might just be a personal issue that won’t apply to every player; after all, I actually didn’t do very well with the breadboards in middle school science class.

Although the rest of the game felt great and puzzle solving was very intuitive with the minimal descriptions, this was one situation where I wish Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles had explicit language outlining the puzzle mechanics. In my opinion, this was desperately needed for the laser section, considering how many dimensions it introduced to the puzzles.

It felt like I was only able to beat these levels through trial and error with virtually no satisfaction at the obtuse solutions. The previous feeling of getting one over on the game designers was nowhere to be found; I didn’t feel like I learned anything. My smile and optimism— gone. For comparison, previous areas took me about an hour to finish, but it took me one hour just to finish the first two levels in Tower 5.

On the subject of game length, Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles is just right. I was able to finish World 1 in about 6 1/2 hours; this felt like a good end point from a narrative perspective, but the game seamlessly transitions into 25 extra levels for World 2. These levels are significantly harder, combining all the previously introduced mechanics plus some surprising platforming challenges.

After another 2 1/2 hours to beat World 2, my final playtime was 9 hours— roughly the same amount of time it takes to beat the first Portal. I didn’t collect all the hidden artifacts, which is next to impossible to do without the ability to backtrack to previous levels, or unlock the achievement that requires you to complete all of World 2 without dying, but kudos to anyone who does.

If you’re a fan of puzzle games, deep sea creatures, and 3D platforming, I highly recommend Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles. Just be sure to take breaks while playing so you don’t go blind from all the neon lights— or go crazy from all the blips and bloops that form this game’s aquatic language.

Our Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles review was done on Xbox Series X using a copy provided by Wired Productions. You can find additional information about Niche Gamer’s review/ethics policy here. Lumote: The Mastermote Chronicles is now available for Windows PC (via Steam).