We interviewed Kouji Kenjou, one of the creators behind the Custom Robo series, and developer Thousand Games’ Synaptic Drive.

Best known for his work on the Custom Robo series with developer Noise, Kenjou was thought to have briefly “retired” from games development around 2006. He returned for Thousand Games’ 2020 title Synaptic Drive (available on Windows PC via Steam, and Nintendo Switch).

You can find our full interview below:

Niche Gamer: Thank you very much for speaking with us Kenjou-San. For those unfamiliar with your prior works, can you tell our readers more about yourself?

Kouji Kenjou: My career in the gaming industry began in 1990 when I joined Namco. I joined the company right after graduating from college. Namco is now NAMCO BANDAI.

I have always been a fan of arcade video games and directed a number of arcade video games at Namco. They are shoot ’em up and puzzle games. Working on the sequels to GALAGA and XEVIOUS was a great learning experience for me at that time. I learned a great deal of know-how from those early masterpieces.

I retired in 1996 and started a company with a few people. Together with my staff, we developed five games in the Custom Robo series, which were released by Nintendo. Now I’m a freelancer.

NG: Your career in videogame began with Namco, and took off with Noise and the Custom Robo series in 1999. Can you tell us a little more about what game development was like at those time?

Kenjou: When I joined Namco, it was a time of transition from 2D games to 3D games. I remember the introduction of 3DCG production tools within the company, and it was very chaotic as everyone was trying to transition to the new era. I also created 2D and 3D games during this period.

During my training when I joined the company, I learned to program on a 2D game board, and just a few years later, I was learning how to use 3DCG tools! But I’m a director, so I’m not programming or painting after that.

After starting my own business, I developed Custom Robo using funds raised by a company called Marigul, a joint venture between Nintendo and a Japanese company called Recruit. The company’s name is derived from Mari (Mario) and Recruit’s trademark gull, a seagull. I am truly grateful to Marigul for supporting the development in every way. That company no longer exists.

In those days, we were able to create large games with much less people than we do now. I think it was different mainly because of the number of people it took to create the graphics. And that was still a time when 3D games were new. Hence, if you made something in 3D, it was relatively easy to surprise the player with just that.

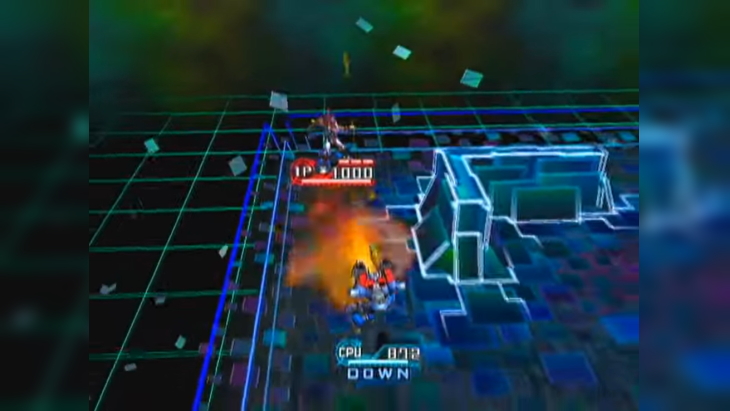

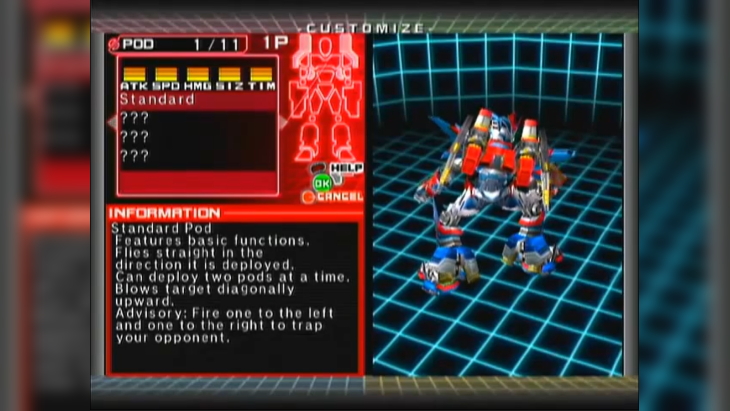

Custom Robo, the first game we developed for the Nintendo 64, was mainly aimed at the elementary school age group, and was received with great enthusiasm because for many of them it was their first encounter with a real and fast-paced competitive action game.

I still have strong memories of receiving comments like “this is realistic and awesome” and “this is exactly the game I dreamed of playing.” Of course, there were plenty of players older than middle school.

In those days, there was a craze among elementary school students to customize “mini four-wheel drive” small toy cars to race each other. Custom Robo was the robot version of that. I have very happy memories of being able to send this game to the children of the time through the great publisher Nintendo.

NG: The series finally came to the west with Custom Robo: Battle Revolution in 2004 (known only as Custom Robo in the west). Did anything change during development or after release once this growth in audience occurred?

Kenjou: The Custom Robo series has been the most representative work of my career. It gave me the opportunity to gain experience in home gaming, even though I had previously only worked on arcade games. I had the opportunity to work with Nintendo, which was a good experience and gave me credibility with the outside world.

Battle Revolution was the first game in the series to be sold outside the country. With the sale of this product, we were able to introduce the Custom Robo brand to people abroad. Thanks to this, even now, we receive comments on social media from people abroad.

When I was a child, my first games in Japan were American-made arcade video games such as ATARI (the first one was probably PONG). So it’s a special feeling for me to have my games known by American players. Of course, it gives me great pleasure to have people from all over the world play my games. I believe that action games are the universal language of the world.

NG: After the final Custom Robo game in 2006 (Custom Robo Rumble or Custom Robo Arena in the west), it is said you retired for a brief time. Would you care to explain the motivation for this, and what lead to your eventual return?

Kenjou: That’s too big a story! I wasn’t retired by any means, but there was a period of time when development wasn’t going well, and as a result, I couldn’t release the product. Later, when I left the company, I was less pressed for time and had time to think about a lot of things about game development.

I was also able to play a lot of games during this period. Among those games, I especially liked Rocket League, Battlefield 4 and Splatoon.

Later, I was invited by the president of a game company I knew to come back to the development field. After working on a couple of games for smartphones there, I moved on to develop my latest game, Synaptic Drive.

NG: If the opportunity ever arose, could you see yourself returning to the Custom Robo series?

Kenjou: Whether I will make that series again? Hmmm, I don’t know about that.

For me, Custom Robo is still a very important game. But if you want to make something that is exactly the same as it was back then, with only the online elements added, that can be done by anyone. I think it should be made by people who have a passion for creating ports. Of course, if the fans want it, it would be great to do it. But it doesn’t have to be me.

I dare say that I still have a lot of feelings about that scenario. Back then, I bought and studied a lot of introductory scenario books. I wrote more than half of the scenarios in the series, and it was a fascinating job that allowed me to go back to my childhood.

I especially enjoyed writing the two Nintendo 64 versions of the stories. They are a series of stories. I think it was a very happy job, because it matched the world I could write about and the needs of the players at the time. But I wouldn’t have to describe the characters’ later lives.

For the Battle Revolution scenario, I only wrote the plot. Mr. Okayasu from StudioFake adapted it to the script. StudioFake did the game development. I produced the entire game. He was one of the developers of Sega’s Rent a Hero and Shenmue. I’m very grateful to him for the way he arranged my plot.

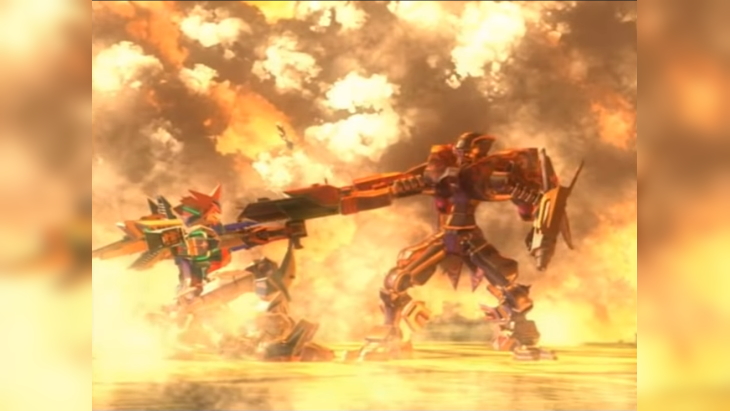

When I was writing the plot of Battle Revolution, I tried to cater to a slightly older age group than the previous games in the series. In Battle Revolution, we made them real young men who fight alongside the police force, and we made the visuals of Robo more realistic and mature.

NG: You’ve now returned to games development through Thousand Games and Synaptic Drive. Did you notice any changes from how game development was 20 years ago to today?

Kenjou: There is now a greater cost to graphics. There is more to think about the online elements. They are different competitive modes, friend battles, and so on.

Development equipment has become cheaper, faster, and easier to create. But it has also made it easier for anyone in the world to make games, which makes it much harder to succeed. Some companies make games with budgets in the tens of millions of dollars, while individual developers make games with budgets in the hundreds of dollars.

But the important thing is how to get the revenue to match the production costs. As long as we can do that, we can make any game we want (well, that’s the hard part…) We have more freedom now than in the past, and it’s a fascinating time in that respect.

And with Telework and Remotework becoming the prevalent style, we can develop together with people who live anywhere, and the time taken up by commuting and meetings has been greatly reduced. Getting the right people together is always a very difficult problem, but basically Telework and Remotework is a very nice thing to have. We can now offer a variety of development styles.

NG: What do you think about Synaptic Drive?

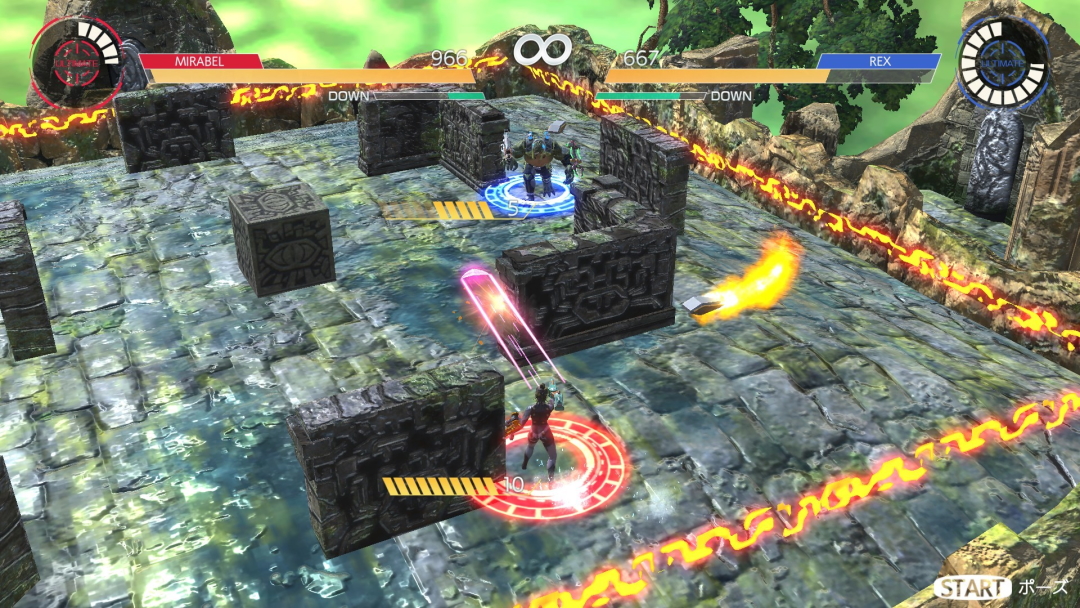

Kenjou: Synaptic Drive was my first game in a decade, so I was able to incorporate different weapons and game systems, and I was able to work on it with a fresh mind. I really like the “Wire” attack system. Devising such a system is more fun for me than anything else.

However, the game didn’t become as popular as I thought it would be. I’m very disappointed that it didn’t live up to the expectations of publishers and players.

I don’t want to talk too much about my regrets, but it was a shame that we couldn’t allocate staff to run the game after launch. There was no budget for it, except for the flaw response, so we barely made a few updates, thanks to the kindness of our limited staff.

And it was also a shame that we couldn’t incorporate a story mode. I had roughly prepared a game system for character backstories and storytelling early on in the project, but for various reasons it never happened. I don’t think it would have been possible to create a story mode as large as Battle Revolution, but I wanted to create a simple story mode.

And while I was working on the game, I also came up with the idea of a 4v4 or more player match-up that would greatly expand on the game systems of Custom Robo and Synaptic Drive, but I knew it would be difficult to achieve. Right now, most massively multiplayer games are free-to-play, and the production costs to sell the additional content are enormous.

We can’t get in there unless we have a lot of capital. If Synaptic Drive had been more successful, though, the chances of its realization might have been higher.

NG: Based on your experiences; do you prefer working as an indie, or in collaboration with large publishers?

Kenjou: This is a difficult question. When I was on staff at Namco, I had some freedom to make. Of course, it wasn’t complete freedom. Around 1990, the big game companies were short on manpower in the arcades, where they had small general purpose board games and large game development work.

On top of that, the number of home games was starting to increase. So there was an easy opportunity for a rookie to be the main director. It was a great experience to have that kind of freedom in my first career.

And later on, working with Nintendo to create games was also an extremely fascinating experience for me. Again, I was able to create with relative freedom. Large publishers have a lot of know-how and organizational skills. It was very reassuring to be able to use that as a backbone for development work.

But nowadays, it’s not easy to create games freely in such an environment. This is a privilege that is reserved for a small number of creators and producers.

On the other hand, I think it’s quite normal for developers to want to make everything the way they want it to be made in an indie setting, if they can raise the money for production (though not all of them do). If anything, I’ve been finding more fun in indie development for the past few years.

NG: Can you tell us anything about your next project?

Kenjou: Right now I’m working as a director of a small smartphone game as a bit of help. After that, I don’t know what’s next, but I’d like to make a new indie game, preferably on a small scale. It might be a competitive game, or it might be my favorite single shoot ’em up.

Starting and releasing a new original project is not easy by any means, but I have no constraints at the moment, so I’ll settle down and think about it. Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity to do this interview.