LSD: Dream Emulator is more appealing in concept than it is in practice. The idea behind this is that it is an early example of a walking-sim, but is based on the recorded nightmares of one Hiroko Nishikawa.

This dream journal was the basis for multi-media artist Osamu Sato, who had already proven himself as an avant gard game designer. Like his previous projects, LSD was not meant to be a traditional video game, and was not intended to be fun. What he achieved is some kind of incoherent interactive installation that happens to require a PlayStation to run.

Even though LSD happens to be very English-friendly, it still manages to impenetrable. While it has garnered a dedicated cult-following, does LSD deserve it? The game does carry with it an undeniable allure and air of mystery… But the air also happens to reek like a sour fart.

LSD: Dream Emulator

Developer: OutSide Directors Company

Publisher: Asmik Ace Entertainment

Platforms: PlayStation, PlayStation 3 (via Japanese PSN)

Release Date: October 22, 1998

Players: 1

Price: ¥628 JPY (approx. $6.00 USD)

If you need help buying games from PSN Japan, you can find our guide here.

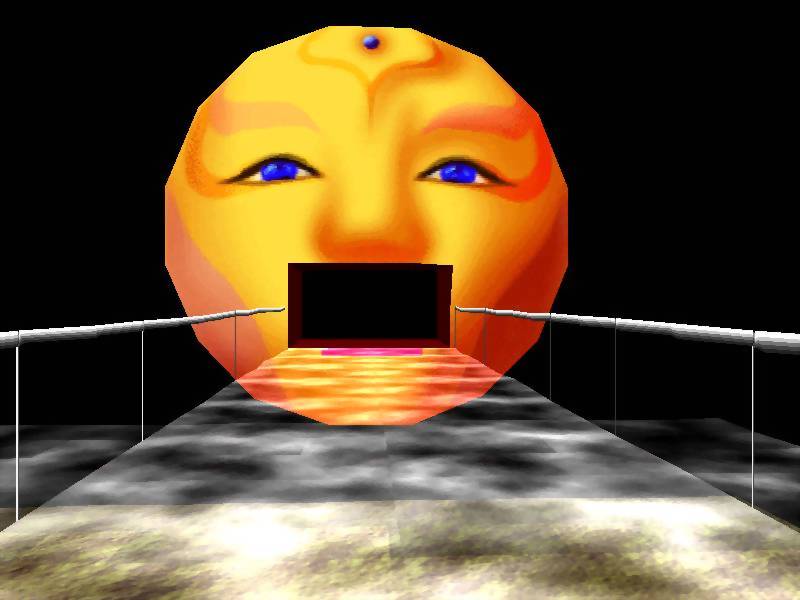

Exploring surreal worlds in the first person with that delicious and nutritious original PlayStation aesthetic seems like it would have been an easy concept to execute. LSD: Dream Emulator seemingly has some advanced procedural technology to make the randomness happen and to alter textures in real time. Why does playing LSD result in such a bad trip?

The archaic controls are forgivable. LSD was an early 3D game on the PlayStation, and was made before the analogue sticks became standard. Playing with tank movement is not even an issue so long as there is the understanding of the historical context. What is not so forgivable is the ridiculously delayed movement.

There is not much to do in LSD. All that the player can do is walk or run around and turn their head. There is no interaction with anything outside of bumping into objects; and with such a simple range of interactivity, one would hope that the feedback of movement would be satisfying.

Rotating left or right is so slow, that CD Projeckt Red could have finished Cyberpunk 2077 and play-tested it in less time. The frame rate is also low enough that the effect of looking around is like a slide show. Strafing is delayed, slow, and can’t be done while moving. There is also a horrible screen shake effect set by default that feels like somebody is violently shaking your head.

By the time this was out, there had already been two Jumping Flash! games that had much more fluid controls. Maybe LSD was a very taxing game for the PlayStation, but it becomes hard to believe when the graphics are made up of extremely simple shapes, and that there is an extremely low draw distance.

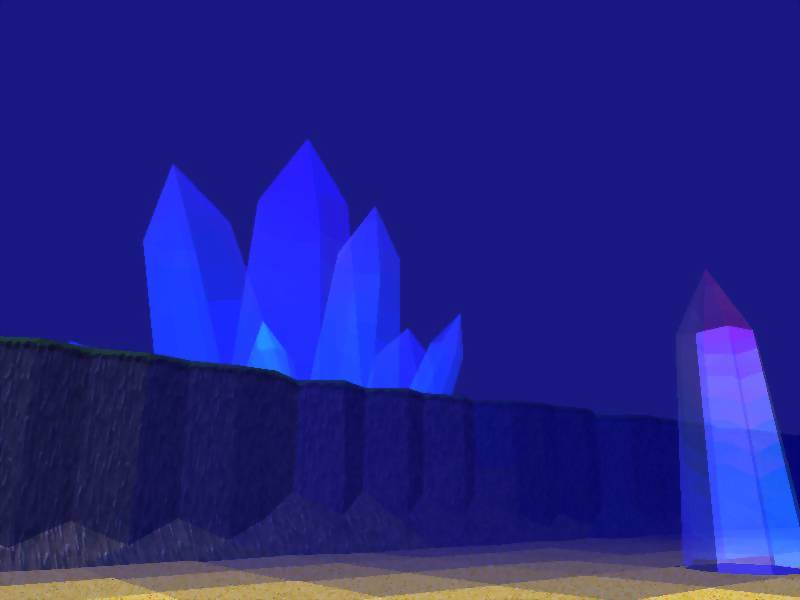

What LSD lacks in comfortable playability, it more than makes up for with its lurid surrealist imagery. Some visual representations of some concepts are quaint in their rendering, but the bizarre architecture and old Asian monk statues that reoccur do make one stop and ponder the meaning of it all.

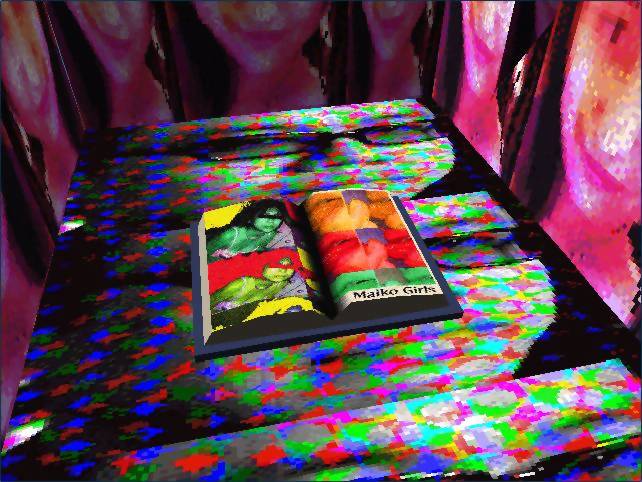

The outlandish geometrical tile patterns or digitized photos that appear warped and twisted are a result of the inaccurate vertices of the PlayStation’s rendering prowess. No matter where you look or go, the visions in LSD always feel wildly unstable and admittedly add to the ambiance of the nightmares.

Everything just barely reads as what they are meant to represent. Things are not well-defined in many people’s dreams, and the almost formlessness and vague suggestions of objects are like trying to remember a half-remembered dream.

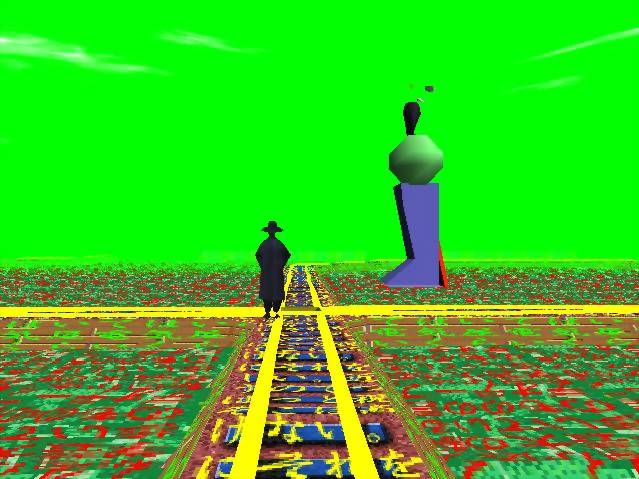

Character animation is also extremely limited. The NPCs in LSD barely move and when they do, you can always expect that they are going to have a very stiff and robotic gesture. The characters did not need to be mocapped, but there could have been more natural looking animation. This came out the same year as Echo Night; another first person PlayStation game that had more believable animation.

Anyone who managed to adapt to the sluggish and responsive controls and forgive the graphics, which were weak for 1998; expect to get even more confused when trying to play LSD. The first things that will happen to anyone who plays this for the first time is that they will struggle with the controls and bumble around in an anonymous room and then walk into a wall.

Walking into a wall or pretty much anything in LSD will shunt the player into a random area. One destination may be a happy fun time zone with running children in the meadow. Another area might be a creepy city where violent perverts hang out and where you are liable to get shot. Then there is the meat-zone where players can enjoy a sumo match between two cardboard cut-outs.

Walking around and seeing these sights is fleetingly amusing. The developers must have thought so too, because you get booted to a chart after several minutes. This chart is a mystery, but is critical to understanding how the dreams work. Every space represents the dream you just experienced, and can give some information on what the next dream could be.

Without a manual, it is impossible to decipher the dream chart. There are guides online that give some information, but it is speculative and does make LSD less interesting if all one does is peek behind the curtain to rob it of the mystery. Bypassing the chart will bring up the starting screen and the next “day” can begin.

The way the dreams work is that the player will eventually begin to manipulate the dream world itself. This is done by doing certain actions like walking through certain routes and by playing LSD a lot. The longer you play, the more the dreams change and seemingly become more unstable.

As states earlier, LSD is not a game that is meant to be fun. It largely succeeds because LSD is very tedious and will cure insomnia. It can hardly be considered a relaxing game, since there are all kinds of horrible things that will try to kill you and send you packing back to the dream chart to start all over.

LSD is all about the emulation of a dream. The problem is that none of the imagery and setting ever feels like a dream. Everything seems far too incoherent, and the choices of ideas represented makes the game feel like it is more about new age philosophy or critiquing Asian culture.

Dreams are too personal to an individual to ever properly “emulate” in any medium. LSD is especially very limiting, since so much of what the game has to show is incredibly vague and disorderly. It does not help that it is also bound by technical limitations of an early 3D game console that has a heart attack when there is more than 1000 polygons drawn.

LSD is not immersive. All the weird visuals stop mattering when there is no context and the meaning could be anything. As a work of art, it fails to engage due to how shoddy the craftsmanship is presented. The obnoxiously loud “clopping” footsteps that never stop because walking to places is how LSD functions.

When things do begin to get interesting, it hardly feels worth all the time put into it. After hours of gaming LSD‘s systems to make textures do weird stuff and tirelessly trudge through low polygon deserts at 10 frames per second, the dreams stop and the nightmares begin.

Shadowy figures begin to be more regular and will eerily home in on where you stand. The game’s mechanics for texture calling gets bugged and the world becomes a frightful eyesore with garish and toxic colors that cause headaches. Oddball NPCs begin to appear corrupted, and it is not clear if it is intentional or not.

The nightmares is easily the highlight of the LSD trip. It is too bad that it requires an absurd amount of patience to experience it. The time it takes to get LSD to go full nightmare is best spent playing anything else.

LSD is unstable nature is also reflected with its music. It can be best described as a cat casually pacing back and forth on a Casio keyboard. Most of the time there is no music at all, just an eerie dead silence and maybe the sounds of birds chirping or buzzing cicadas.

The cost of a physical copy of LSD: Dream Emulator is utterly outrageous and insulting. Many listings are between $600 and $1,000 range. No game or piece of interactive art is worth this much, especially since the experience offered is completely hollow. It is hardly worth the six dollars on Japanese PSN and is best experienced as a Let’s Play on YouTube.

LSD: Dream Emulator may be one of the most over hyped cult classics on PlayStation. The idea of it is so much more appealing than the actual game. There aren’t too many “dream emulators” out there and it just goes to show how people will latch on to something that fills a void, even if it is incredibly rough and boring. If anyone offers to play LSD: Dream Emulator with you, just say “no”.

LSD: Dream Emulator was reviewed on PlayStation 3 using a personal copy. You can find additional information about Niche Gamer’s review/ethics policy here.

Images: GameFAQs