Many years ago, when writing a review for Divinity 2, I made an observation about gamer’s perception of European roleplaying games that I felt summed the situation up perfectly. In that review, I made the comment that European CRPGs are like plus-size women. To most, they are seen as aberrations that are wholly undesirable and deserving of ridicule. Yet to others, they are seen as a pleasing diversion from the norm that have uncommonly desired but still sought after features that some find attractive. In other words, what most gamers find annoying and intolerable, a small percentage of their brethren find charming and unique.

European CRPGs are, as anyone who has played any within the past 15 years can tell, markedly different than their American-made counterparts. This difference is seen most strongly in the combat and world navigation systems, which are often very hard to grasp or lack the kind of feedback and ease-of-use that most gamers have been taught to expect. Lacking instantaneous fast travel options, quest markers, and having melee attacks that are often difficult to pull off without hours of practice, many mistake them as having been poorly designed. In reality, they are merely emulating the style of CRPG that existed in the 1980s. A style that, unlike America, Europe did not abandon.

To understand why that is so, you need to look at the European RPG scene of the 80s and 90s. While the JRPG slowly rose to dominance in the west thanks to the NES and SNES, the PAL territories of Europe didn’t enjoy such a renaissance. While American gamers like myself complained about only having three out of the six available Final Fantasy games, Europe didn’t get any of the first three western-published Final Fantasy games until the Playstation reissues in the early 2000s. Even after the series became popular thanks to the mainstream success of the 7th installment, Pal territories had to wait an entire year after the US launch before it was released on their side of the Atlantic.

This is still somewhat of a problem, with Atlus gaining a somewhat nasty reputation amongst European RPG fans for delaying or even cancelling physical releases of their games for their own territories. Though it’s nowhere near as bad as the last two decades of the 20th century, it’s still something many European RPG fans have to deal with whenever a new game is revealed for the west.

This lack of JRPG influence prevented Europe from adopting a lot of what Japanese RPGs became famous for starting. The easier-to-learn combat, the story-heavy design, the smaller and more linear worlds…European gamers were never over-exposed to that style and therefore turned to the only thing they *could* find on store shelves: PC RPGs.

Though America had a strong enthusiast PC culture in the 80s and 90s, it was even bigger over in Europe. Since consoles were outrageously expensive and many were forced to import games at high prices, it led to people gaming on their PCs instead.

It was much cheaper to simply cobble together an IBM compatible than to buy a gaming console, and often led to a much more diverse library of games as well. With PC gaming unhindered by the NTSC/PAL territory nonsense and lax piracy laws allowing for easy distribution of software, enthusiast PC gaming in Europe was even bigger than it was stateside.

A good way to illustrate the difference is to take a look at the chip tune scene. In America, chip tune artists predominately use the NES and Genesis sound boards to make their songs. In Europe, especially Sweden, you have people making chip tunes with the Amiga or Commodore SID chip. The scene is so competitive and professionally handled over there that major American artists have stolen these tracks to add to their own. Google “Acidjazzed Evening” if you don’t believe me.

So rather than be influenced by Final Fantasy and Dragon Warrior as we were here in the states, your average European gamer grew up on grittier, more challenging fare like Wizardry and Ultima.

You could also say that the Japanese RPG never really caught on with most European gamers since they wanted their own identity and many CRPGs at the time that were either developed or published by European companies were ignored by the rest of the world.

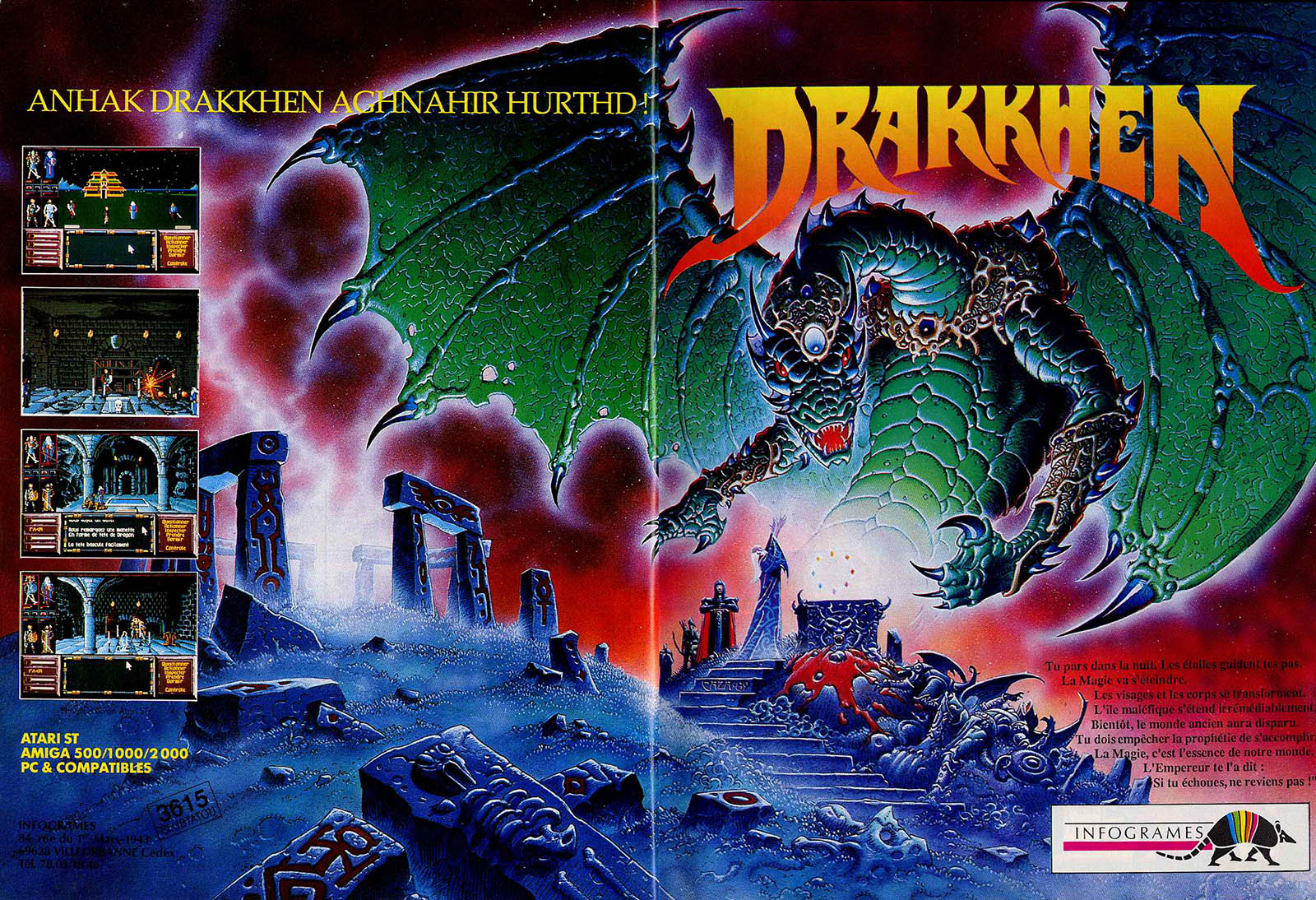

Looking at French-based Infogrames (Now known as Atari) and their cult-classic CRPG Drakkhen and how it didn’t do too well when published by a Japanese company for the SNES tends to support that theory. European RPGers were making their own offshoot of the main RPG hobby, and they drew upon the classic DOS titles of the 80s when looking for inspiration.

This sub-genre of European CRPGs went largely unnoticed by American gamers through most of the 90s, but that lack of awareness would change with the resurrection of the PC RPG in the states. With Fallout, Baldur’s Gate and Might & Magic VI creating a resurgence of the CRPG after a long hiatus (A story for another time, involving SSI and the decay of the Goldbox titles), the desktop computer once again became a hot platform for roleplaying gamers. This, in turn, led to money-hungry publishers looking for new titles to bring to the RPG-starving Americans who just built their brand new Pentium 2 systems and were looking for something else to sink their teeth into.

Starting in 1999, a writer for Gamespot by the name of Desslock began covering an odd-looking European CRPG by the name of Gothic. Though it was pre-alpha and what few screenshots he posted looked very crude, it gained quite a bit of attention. So much attention that by the time it was released in 2001, an online community had already sprung up to welcome it.

Though Gothic’s combat was hard to adjust to and the graphics were nothing compared to Bethesda’s Morrowind (which would come out 6 months later in May of 2002), it contained many features that were long thought abandoned by western CRPGs.

With genre darlings like Baldur’s Gate and Might & Magic VI being fairly linear RPGs with heavily scripted character interaction that was the same during every trip through the game you’d take, Gothic harkened back to the Ultima series with its non-linearity and complex NPC interaction. Unlike its contemporaries, Gothic had advanced NPC scheduling, non-linear pathways to the ending, complex faction play and a bevy of dialog-based quests that encouraged actual roleplaying rather than simply taking out your weapon and killing things. To many, this was new. Though to older gamers who grew up with Ultima 7, this was merely a re-introduction of long lost gameplay mechanics that were desperately in need of a reappearance.

Though Gothic didn’t outsell Morrowind, it did manage to create a strong interest for more of the games in the states. Enough of an interest for several European-based publishers to take a risk and begin sending their games stateside. Thanks to Gothic’s success, and the European CRPG renaissance it kicked off, several of the most beloved CRPGs of the 2000s were made by developers who were not from North America or Japan.

France gave us Arx Fatalis. Belgium gave us Divinity. Germany gave us Spellforce, Drakensang, Sacred, and more Gothic sequels. Poland gave us The Witcher. You could say that Europe in the 2000’s was akin to Japan in the 1990s. They pumped out top-quality RPGs that defined an entire generation and still stand today as some of the best the genre has ever seen.

So why did these European CRPGs do so well? Other than bringing back those abandoned features games like Ultima and the SSI Goldbox series used in the 1980s, they also prided themselves on being very dark and depressing. After all, you don’t name a game “Gothic” and have it be about a young man fighting an evil empire and getting to kiss the girl in the end, right? Of course not. For European CRPGs, a story had to not only make sense but also make you cringe.

Since I bring it up quite a bit, let’s talk about Gothic‘s story. You begin the game as a man shoved into a violent prison colony against your will and only a minute later, get beaten to death by a group of convicts. You are nearly naked, penniless, with no weapon and no combat skill, yet you have to find some way to survive your incarceration long enough to plan an escape. You find a wooden stick, swing it at a few enemies and die horribly. You can’t level-up, you can’t kill anything and enemies are chasing you from all sides. Chances are, if you were like my friends who I tried to get into the game, you gave up out of frustration and never looked back.

The trick? You limp to the nearest settlement and begin to manipulate the prisoners in an effort to ingratiate yourself to their leader. You climb up the ranks of the local worker’s camp until you earn enough respect to not only be allowed some armor and a weapon, but get protection from the people who will gleefully pound your face into the dirt every time you pass by them.

Perhaps the long history of war and the burden of western civilization is what makes their games so dark, or perhaps it’s just a response to the overly bright and optimistic stories told by the rest of the hobby. Whatever the reason, it’s often this grim realism that keeps people coming back to European CRPGs.

In the last five or so years, many of the features in these games have begun to show up in other titles. One good example is Dragon’s Dogma, a game that not only takes the familiar “story of darkness” route that European CRPGs often do, but even emulates its deep and hard-to-master combat systems as well. Dragon’s Dogma was a very odd game for a Japanese developer to create, yet it did rather well even with its old school CRPG mechanics and design.

Though many may scoff at me claiming this, Dark Souls borrows heavily from that style as well. The brutal combat, the overly dark storyline, the “deck stacked against you” design…it is painted with a European brush and there is no denying it was influenced by European CRPGs. Though anecdotal, I’ve seen it mentioned dozens of times on various forums about how “European” Dark Souls plays, which is a view I wholeheartedly share.

Partly due to the (re)adoption of these once abandoned features into mainstream games, a lot of the uniqueness and charm in European CRPGs has been overlooked for the past five or so years. European developers are still crafting genre-redefining games, but most of their efforts are overlooked as both American and Japanese studios absorb those ideas into their own games. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, since the past decade’s European dominance has helped bring us to an age where complex CRPGs like Divinity: Original Sin and Wasteland 2 can not only get funding but sell outrageously well.

Though Gothic may never get another sequel and Spellforce’s next installment is being developed by an untested studio, the European CRPG still lives. The tremors caused by games like Sacred and Arx Fatalis are still being felt more than a decade later.

Last but not least, we should thank them for strengthening the RPG genre at a time when publishers believed simplicity and player coddling was more important than challenge and depth.