Many allegations have come against Dangen Entertainment and its CEO Ben Judd, after a Medium post by an anonymous author made allegations of incompetence, refusing to pay developers, Judd preying on younger female developers, and more. Afterwards, Dangen attempted to refute these claims, and further claimed the author had participated in organized sabotage, slander, and attempts to gain titles published by Dangen to publish herself.

The now deleted post to Medium titled “Dangen Entertainment Warning” was posted on November 29th, detailing the alleged failings and unprofessionalism of Dangen, and CEO Ben Judd’s allegedly predatory behavior. Judd is also alleged to have acted unprofessionally as Vice President of Digital Development Management Agency Japan (DDMA).

The medium post’s author claims they are not the lead developer of Devil Engine or Fight Knight (both games Dangen published), but were “a key member of these projects at the time,” initially being part of the team that made Devil Engine. The author also states others disclosed information to her on a need-to-know basis, or from those volunteering the information.

At over 9,800 words, the post made numerous allegations in what appears to be chronological order. You can find the full run-down on the allegations below:

Allegations Made Against Dangen Entertainment

The beginning mentions that Judd had allegedly made advances on both the author and “Alex” [1, 2], and both had similar experiences with him.

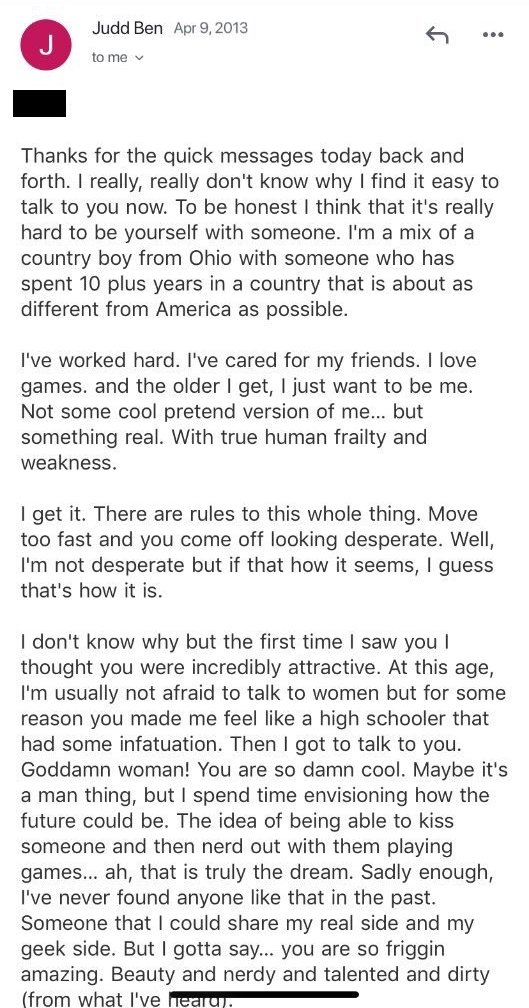

Alex received an alleged email from Judd’s business email later led to an email from his personal email. The latter email (on April 9th, 2013) attempted to flirt with Alex.

Judd allegedly said similar to the author “almost verbatim” but was never propositioned. “He often talked about how he was a shy country boy from Ohio at heart, a nerd who forced himself into acting lessons to overcome his social anxiety, a washed up older man who just wanted to connect with fellow gamer women, etc.”

Alex would later enter a relationship with Judd “before gamergate year” (est. 2014) and the dating continued “well into that.” Alex was a “fresh graduate”, while Judd was 12 years older than them (Alex 24 at the time) and came onto her.

Alex then explained how Judd “made us pretend we were strangers at the [industry] meet ups.” Other women had approached Alex with accusations, which they brought up to Judd. Judd dismissed them, stating there was “another side to the story.”

Alex later tweeted allegations that Judd took advantage of having “direct access to young, vulnerable devs often desperate for a break.” However, the Medium post made no specifications about Judd ever putting Alex in a position where it was implied she would lose her job if she was not involved with him.

The post then focuses on Dangen’s alleged incompetence when publishing Devil Engine and Fight Knight.

Fight Knight‘s lead developer was approached by Dangen, offering a free Japanese translation of his Kickstarter demo. Later signed on with Dangen once the Kickstarter campaign ended. The author worked on Devil Engine, and the two development teams became friends after the Fight Knight developers recommended Dangen as a publisher. Both teams had positive experiences with Dangen for most of 2018.

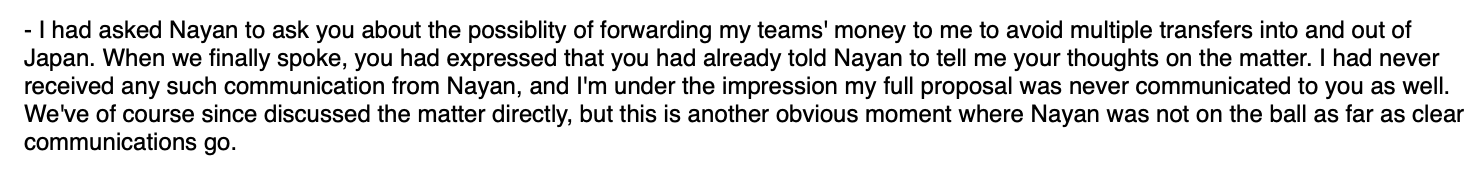

The post goes onto to describe unprofessionalism of both Nayan Ramachandran (Co-Founder & Content at Dangen) and Dangen staff at large.

When Ramachandran wished to update the contract with Fight Knight to include a Chinese language version, he “forgot to use the original FK [Fight Knight] contract and instead simply edited a boilerplate Dangen contract with all of the original negotiated clauses reverted.”

A developer had spent $400 of his own money to have a lawyer examine the original contract. The author would go on to negotiate and write another contract for another “developer friend” who successfully pitched to Dangen in January 2019

When examining the initial contract, the developer and the author noticed many “concerning clauses,” including a loophole “that allowed Dangen to charge whatever they liked to FK’s expenses without his approval.” The author allegedly rewrote the new contract, which Ramachandran agreed to and Judd co-signed.

The author also alleges “Nayan and other Dangen staff’s lack of communication and in some cases outright lying regularly derailed the development schedule.” In one incident the Fight Knight team were approached to produce a new and exclusive trailer for a popular gaming stream event (Kinda Funny Games). When Ramachandran claimed he had not received the forwarded email, the developers “put aside working on the last level of the game in order to put a week into creating this trailer.”

Despite this, Ramachandran would later give “only a few hours” notification for the lead developer to make a video speaking into the camera for the event. This video would end up not being used, and it was later revealed by Ramachandran to be optional, and not urgent.

Dangen also requested a new Chinese Nintendo Switch build of the game. Final levels were delayed to get the Chinese fonts working in GameMaker Studio 2. Requests for assistance from Dangen (including having the title still rhyme in Chinese, and requesting if they could place a Chinese copy on Steam), but no response was given.

“Ultimately preparing the Taiwan demo took half a month away from completing the game. We saw little to no change in wishlists from this event, which is unsurprising considering a Chinese localization of the Steam page was never prepared.”

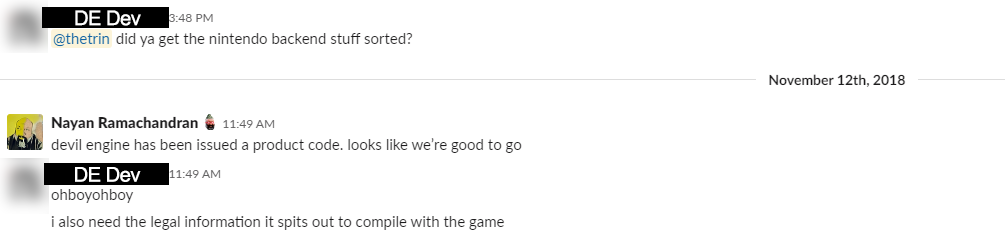

Devil Engine allegedly suffered as well. Ramachandran insisted the game’s release be delayed from October 2018 to February 2019, to allow for more paperwork to get the game on Nintendo Switch, and prepare more marketing. Despite this, legal troubles arose in late 2018/early 2019, with a third party developer. “The situation was quickly deteriorating, and Nayan ignored most of our repeated requests for help.”

Dangen would later refuse to upload the game’s soundtrack to Steam, wanting to set up the soundtrack on Bandcamp for a simultaneous release. They blamed the delay on “the setup process of a Japanese Paypal business account.”

The team explained that Bandcamp could allegedly collect money without a Paypal account, pointed out that the delay had been to help with release support such as this, and that Devil Engine was “the only game Dangen had release in 2019” since Witch’s House in October 2018. Dangen would go on to publish Minoria (August 27th), Disc Creatures (October 17th), and Bug Fables: The Everlasting Sapling (November 21st) in 2019.

Nonetheless, the author alleges that “as of this writing, Dangen has not sent us a single cent of money from the Bandcamp sales of the DE [Devil Engine] OST.”

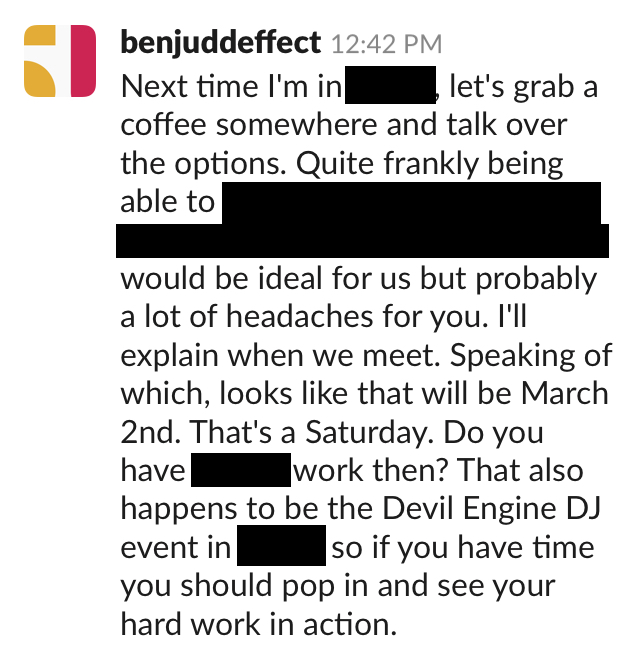

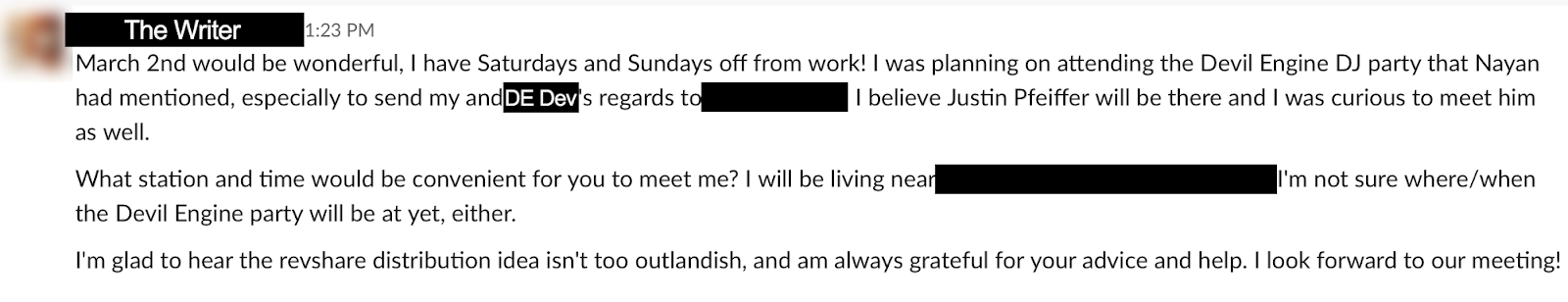

Judd then allegedly offered to reach out to the author in March 2019 to solve these issues. This meeting took place at a nightclub, which was hosting an event to play Devil Engine‘s music.

The alleged meeting quickly turned away from being professional to rather awkward flirting

“When we met, we discussed business for about 5 minutes, and then he changed the topic to my personal life. He complimented my “skill sets” and asked me many personal questions about my background and my future career plans.

[…]

He also asked me about my romantic life, and specifically asked if I was dating developers he knew that I was working with. When I said that I wasn’t dating any of those people, he asked me what I thought about dating in “nerd communities”.

He said something to the effect of, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but you’re a very attractive young woman. How exactly would a shy, nervous nerdy guy ask you if you’re interested in dating without offending you?” “

While the author then explained that it was fine if the woman accepted the advances, and how dating work colleagues is a bad idea, Judd allegedly became frustrated.

“This answer seemed to frustrate Ben, and he exclaimed “how’s a guy supposed to date anybody if you’re not allowed to let a girl know she’s attractive to you?” and some things about how hard it is for men to date. I felt the conversation was very strange, but continued to assert that there was no harm in just politely asking a woman if she was interested in dating so long as you respected her saying no. The topic of dating seemed very sensitive for him and I wanted to change the subject.”

Judd allegedly continued to interact with the author. Though more professional, he would allegedly reveal “stories” from his work with DDMA, breaking NDAs. These various stories included:

- “The CEO of Playism is, in Ben’s words, “a cheap asshole” who forced Nayan and Dan Stern (another Dangen employee) to sleep in net cafes instead of allowing them to sleep in proper accommodations on business trips. He brought this up to explain why he always made sure to accommodate people in proper hotel rooms when I requested funds for my stay at Bitsummit 2019.

- Unties, Sony’s indie games publishing branch, is going bankrupt. I was apparently told this so Ben could express how difficult the indie market is for publishers. He claimed that even a giant company like Sony had no choice but to be subject to the whims of the market.

- He was working on the deal for Sekiro between Activision and FromSoftware. According to him, Activision and FromSoftware hate each other. This was a story shared with me to explain why he was tired and late to a meeting.

- Devolver [Digital] and FromSoftware hate each other because Devolver failed to properly handle withholding tax forms for Metal Wolf Chaos, causing millions of dollars and months of unnecessary loss.”

- 505 made mistakes when releasing Bloodstained that will cost Koji Igarashi millions of dollars.

The latter two both had screen captures of Judd’s alleged Slack messages about those stories.

Continuing, the author states how they used unpaid work to help defuse issues caused by Dangen’s “lack of communications, lying, and incompetence. I had to stay polite and neutral as Dangen’s behavior became increasingly less acceptable, and I had to repeatedly speak with Ben in private over phone or text and endure his repeated and empty stories about being “an older man who just wants to do right by young and vulnerable indie developers”.”

Devil Engine had additional problems with its release, some which were omitted by the author themselves. Despite this, Judd shared with the author that the game sold roughly 3,000 units during its launch month.

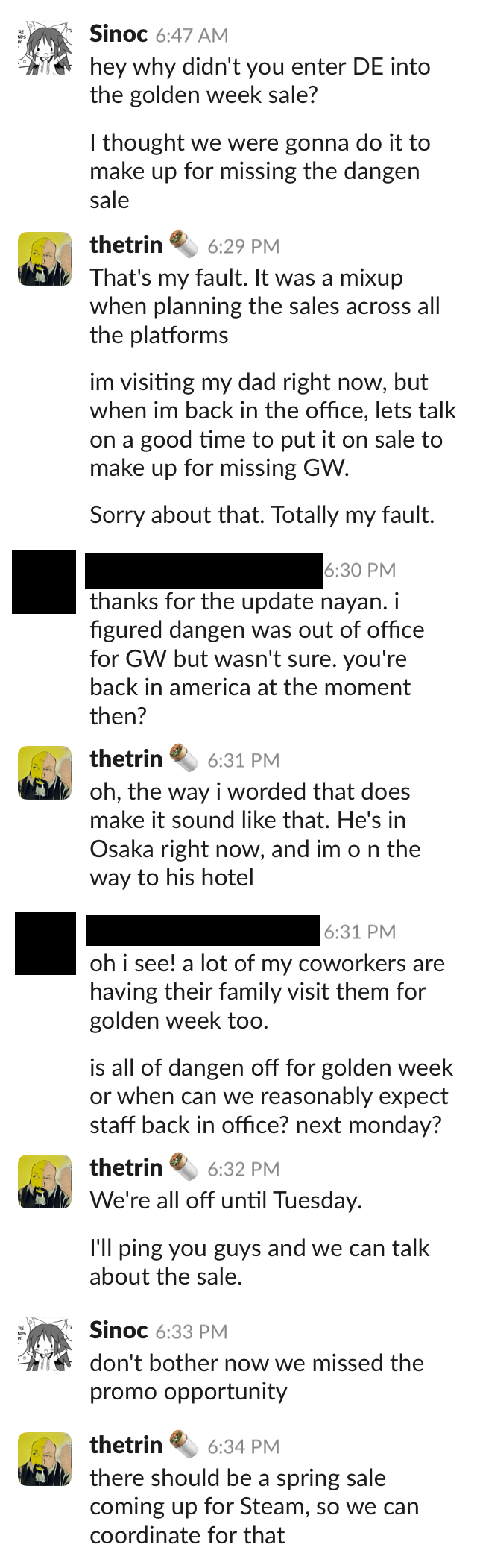

Ramachandran suggested the game be included in the Steam Golden Week sale (Golden Week being a Japanese public holiday which the author claims is the country’s most popular holiday season), yet the game was never included.

The author claims the sign-up process “Could have been done within 5 minutes”. Another member of staff spoke to Ramachandran on Slack.

The author states that “Dangen staff almost always had some excuse about why they couldn’t answer in a reasonable timeframe. They often blamed timezone differences, claimed they were out of office, or on some sort of company holiday. If developers had a question on Wednesday night, it often went unanswered until the next Tuesday, if it was ever answered at all.” The author even claims Ramachandran had been playing games (notified on Discord and PlayStation 4 with employees he had friended) at times he should have been answering requests.

In addition, Dangen staff took off half a month for Golden Week 2019 (the longest ever due to the changing of the Emperors), making then unavailable to the month prior of Bitsummit, “one of their biggest promotional events in Japan.”

This was further soured as Dangen staff “made sure to travel around Osaka filming themselves drinking in bars and talking about videogames to celebrate their anniversary! This stream was populated by roughly twenty (20) viewers, a majority of whom were Dangen developers.”

The author cited the video only having 115 views at the time. Later in the post, the author criticized Dangen’s focus on these live-streams due to their low-views, and often not playing video games and instead showed them “drinking and enjoying the nightlife in Osaka.”

The alleged lack of professionalism continued, with a third party publisher reaching out to the developers claiming Ramachandran “had treated them extremely poorly” and gave no definitive answers on if they wished to publish Devil Engine on physical media.

Seemingly, none of the developers even knew about this opportunity. Two members of the team (Joseph and Sinoc) finally lost their temper. Judd reached out to the author to discuss the issue.

The result of the call meeting had Ramachandran and other Dangen staff being told to forward all their communications to the author; regarding Devil Engine, Fight Knight, and other projects the author was involved with.

Soon, the author allegedly saw “at least” four third-party offers to put Devil Engine on physical media from months prior. None of these were conveyed to the team, or pursued by Ramachandran.

The author claims they “took over as the third party publisher negotiator, a task that grated on me immensely as Dangen still demanded they receive 40% revenue share of any such third party deals, regardless of the reality that Dangen’s involvement had actively been a detriment to the proceedings and caused harm to our reputation.”

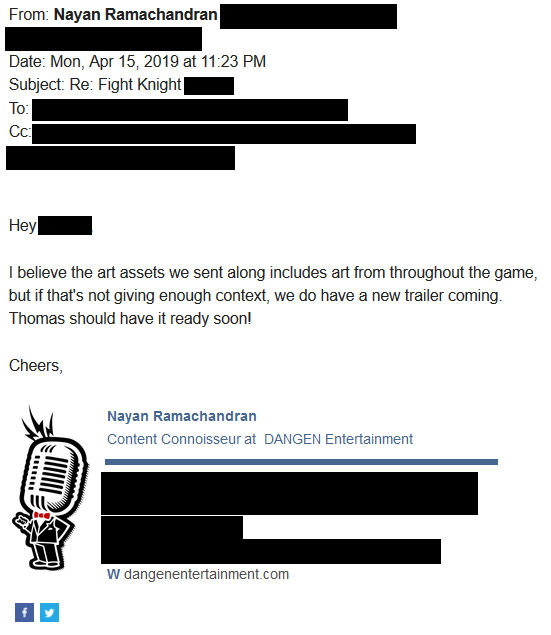

This poor relationship with third parties extended to Fight Knight, where a publisher asked “if there were new assets available for their designers to use.” Ramachandran replied without the lead developer’s consent, with an alleged lie.

It seems the author used the wrong images, as the first image in that section is a duplicate of another discussing Devil Engine coming to other platforms, and the developer then begins discussing a release date, despite neither image discussing it.

In any case, the author claims that Fight Knight was now being released in July, and the team had no plans to make a new trailer. The developers could not correct Ramachandran, as it would make both of them look unprofessional in front of the publisher.

A Fight Knight developer confronted both Judd and Ramachandran on Discord. When Ramachandran then asked for a new estimate, the developer further clarified that the issue was communication as a whole. Ramachandran later apologized to the developer in private messages.

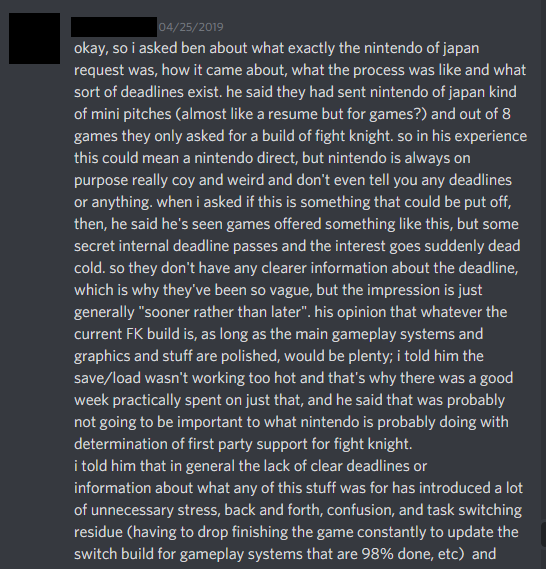

In early April, Ramachandran asked for an urgent new build of the Nintendo Switch version of Fight Knight. Allegedly this was “the fifth or sixth time Dangen asked for a console build suddenly in the middle of development.”

The developer seemingly had no idea the game had been pitched to Nintendo, and all marketing decisions were supposed to be subject to approval by the developer. For a “new” build to be requested, the author alleges Dangen had sent a build to Nintendo without the developer’s approval (which the developer may have considered unfinished and unpolished).

As completing a new build would delay the final game, a developer asked what Nintendo were hoping to see. Nintendo Switch exclusive features would now be impossible since the notification was so short, and time was being spent on the commitments to the PC version’s Kickstarter goals.

Ramachandran stated there were no details, but the build bad to be finished by April 19th, 2019. Ramachandran also confirmed Nintendo had seen a prior build. The author pressed Ramachandran for which part of Nintendo made the request (Nintendo of America or Nintendo of Japan), only for Ramachandran to reveal Judd was the one in direct contact, not him.

After a call with Judd, the author conveyed what was allegedly said to the Fight Knight developer. Judd had confirmed he has always been the one in contact with Nintendo, rather than Ramachandran.

Ben took to the company Slack, asking why the earlier November build had not been sent to Nintendo. Judd called Boen and was “very apologetic” with most of what was said being similar to what was said to the author earlier. While the build was completed on time, the team never heard whether this was sent to Nintendo or the result. Fight Knight is currently available on Nintendo Switch.

The author also criticizes how Dangen would be involved with interviews, instead of the developers themselves and their role as publisher [1, 2, 3].

“As basic support for their games fell by the wayside, this obvious self-aggrandizing bent to Dangen’s marketing began chafing on a majority of the developers under them. There was an impression that Dangen Entertainment was more interested in promoting their image as a” struggling startup indie games publisher staffed entirely by foreigners in Japan” rather than promoting the actual games being published by them.”

Dan Stern (Developer Relations for Dangen) also allegedly lied in an interview with GameIndustry.biz, stating they made money through royalties of game sales, and they did not charge developers separately for each service (support, localization, and porting for example).

The author claims that Dangen does charge for localization, separate from royalties, and paid before developers receive their share of revenue. “For games with extremely long scripts, localization costs can be almost $25,000 USD per language – a huge burden which could mean that some developers may never see royalties accrue.”

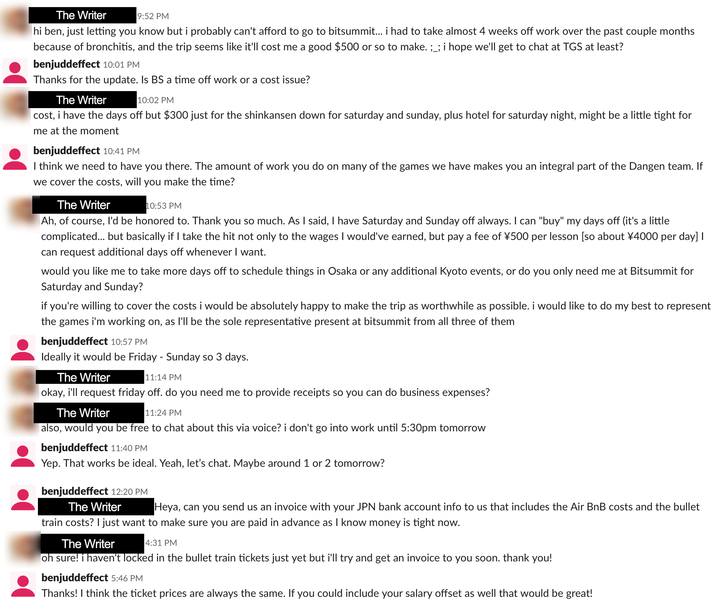

Continuing, the author explains how Judd asked if the author could go to Bitsummer 2019. While the author declined due to the expense (a cost of around $500), Judd said it was “absolutely critical” she attend. He agreed to pay for her travel expenses, time off work, and hotel.

Judd also stated she was free to pay any price for a hotel, rather than share a room in the Dangen staff Airbnb “around a bunch of stinky guys who snore.” While the author found Judd’s assumption that she would have shared a room with Dangen staff, but dismissed it as she was “used to Ben saying odd things like this.”

When the invoice was sent to Judd, he “suddenly ignored” the author, and no money was sent. While Ramachandran stated this was due to the Japanese banking system (and they were only able to send money on a Friday), she finally received the money “a few days before Bitsummit on a Sunday” after weeks of requests.

Around this time, developers beyond the Fight Knight and Devil Engine teams had taken issue with Ramachandran’s alleged “laziness, incompetence, and lies.” On May 11th Judd wanted to discuss the Devil Engine project. While the author had avoided naming Ramachandran, Judd brought up firing him, and hiring the author as a replacement.

Judd then asked for a writeup on the grievances against Ramachandran, and collect more complaints from others who wished to remain anonymous. The author did so, and included her own proposals to fix the situation, and issues her “promotion” could cause. Judd’s reply seemed to indicate he was on board with this.

Judd had dealt with the author before Bitsummit 2019. After the event, the author reached out to him for what would happen next. Judd arranged a call with the author 10pm on an undisclosed day. The call began with Judd seemingly taking issue with how one of the Devil Engine developer’s complaints were getting “hard for them to field.”

When the author defended the developer (“Yeah, he can get a little spicy sometimes.”) Judd made it clear he felt the developer was being abusive (“He’s not spicy, he’s toxic.“).

Later in the post, the author states that the developer was “the warmest and friendliest to Dangen,” and while he used foul language and decried Dangen’s professionalism, allegedly never made threats. Judd would later allegedly ask that developer to only speak to Dangen staff with “yes” or “no” answers.

Despite the author’s attempt to explain why the developers would be angry, Judd made it clear he was dissatisfied with how the teams were operating, and that he would even punish the Devil Engine team for the actions of the Fight Knight team.

“Ben snapped that if FK’s dev couldn’t be satisfied with Dangen’s service as is, then he would have to consider dropping support for DE. Ben claimed that while they had had a lot of great opportunities lined up for FK, such as Google Stadia, Epic Games Store, and Nintendo Direct, if our contract stipulated that they had to come to us with “granular” approvals all the time, then they would have to allow such opportunities to pass us by.”

Considering the Devil Engine team had not received any of their revenue share yet, the author felt he was using this to threaten the Fight Knight team into surrendering control over Dangen’s marketing activities.

While the author asserted that the two projects were different, Judd seemingly took Ramachandran side. “Look, I see what you’re doing. You’re running around behind Nayan’s back, trying to ruin his life, digging up gossip about him. It needs to stop. I will not tolerate my team being treated like this.”

When the author pointed out she only collected grievances against Ramachandran after his request, Judd quickly focused on the author’s offer to join Dangen. “I’ve been very impressed with you. I think there’s a real opportunity here at Dangen for you.” When the author explained how the job offer would not affect the conversation at hand, Judd became aggressive again.

“Do you want to be an [####] forever? Is that what you want?” We assume “[####]” is either an expletive, or a job title. The author then explained how she had spent time and money training for her current career. Judd abruptly ended the phone call, to tuck his daughter into bed. The author claims she “had never heard about his daughter before this call.”

It was later revealed to the author that Ramachandran had spent a night drinking with Judd [1, 2]. While it was not confirmed that was the same night, it may indicate Judd and Ramachandran were close friends.

Before Bitsummit 2019, Judd asked the author to change their meeting location from Kyoto (where the convention was being held), to Dangen’s offices in Osaka. While Dangen staff the author met had no idea about the meeting, they directed her to Judd.

Judd then asked the author to leave her suitcase in the office, so the two could speak in a cafe away from the office building where other staff could not overhear them. To prevent Judd from going back on his word later, the author asked is she could record the meeting on her phone. He agreed.

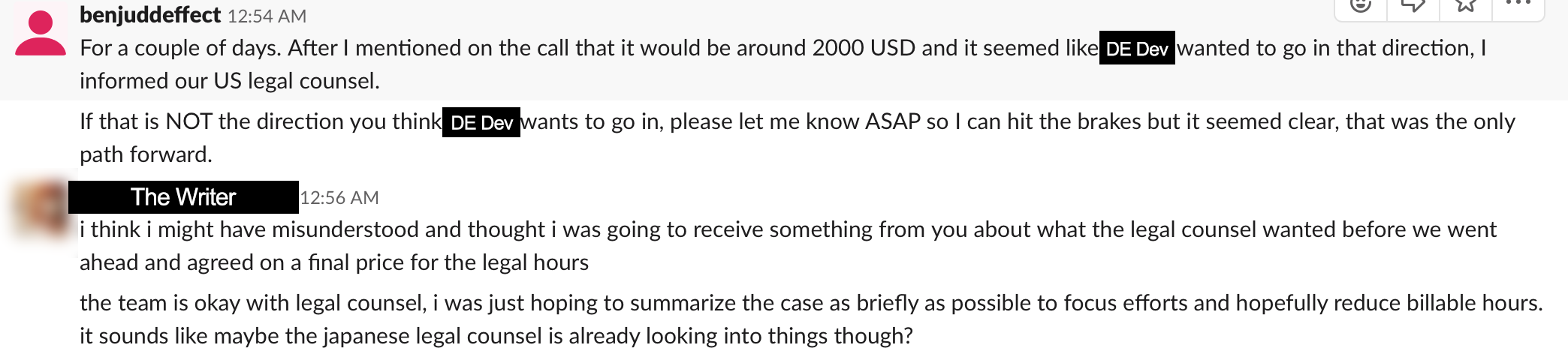

During the meeting, Judd offered to pay the Fight Knight team $400 to cover the legal fees due to the earlier issue with the contract (at this point claiming Ramachandran had lost the original contract). In addition, the Devil Engine team would be paid for the approximate lost revenue from the Golden Week Sale they missed out on.

Judd then shifted focus to formally offering the author a job at Dangen. The offer was roughly $500 per month, but not on a full time basis. The author reiterates that she was already doing a huge amount of work for only the share of revenue from the development teams, and that (due to Japanese law) Ramachandran must have been paid roughly $3000 per month.

Judd also “stressed that he was very eager to finally hire a minority woman onto the team, and that he had been looking to make his company more diverse,” and that he was upset that when John Davis left, Dangen had “little diversity on the team.”

Despite the author’s assertion that her skills were more important than her race and gender, Judd “insisted that diversity was important, as different backgrounds meant different opinions, and this would strengthen the company.” The author asked Judd to let her consider the offer, and rejected an offer to go to a dinner party before Bitsummit.

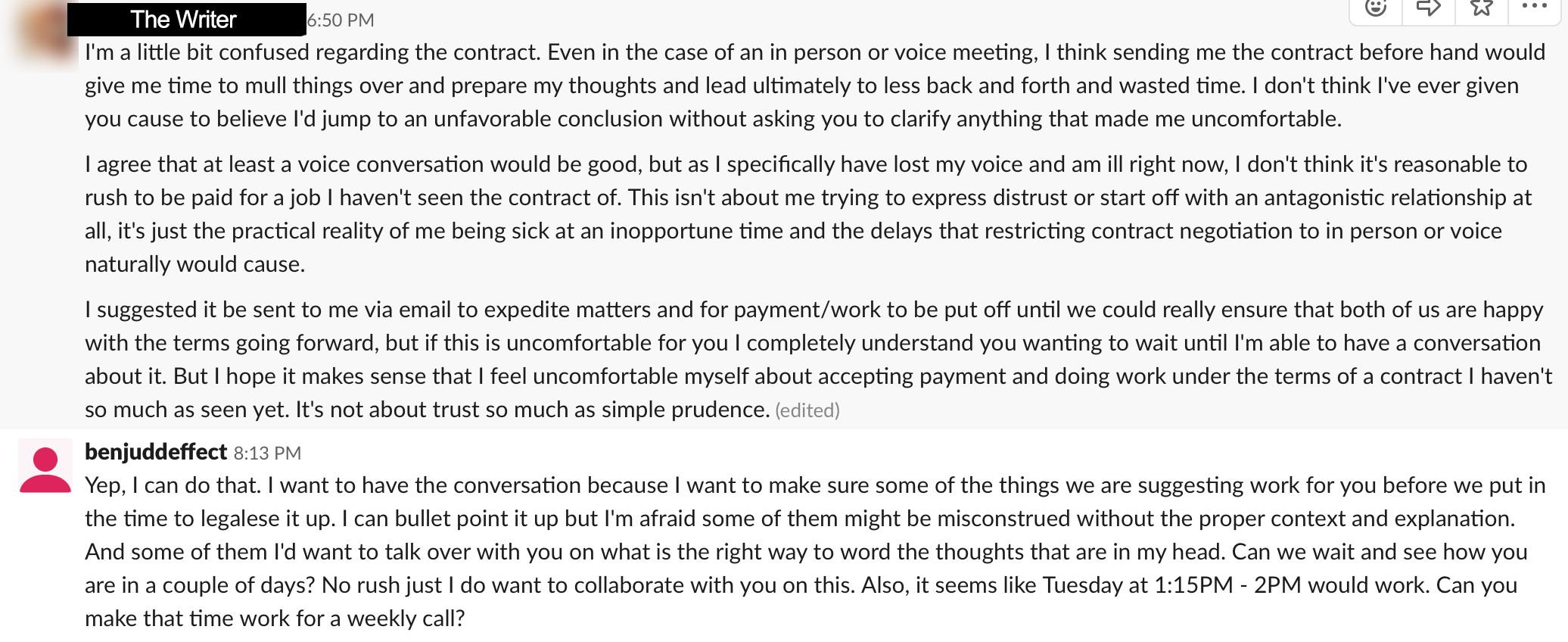

Later, the author decided to take the offer, and hoped to negotiate a better contract. As Judd was busy with E3 and work with DDMA, the contract was only discussed on July 1st- when the royalties for Devil Engine were due. This led to a planned face-to-face meeting on July 4th, however the author became ill and lost her voice.

Judd allegedly refused to send the contract to the author via email, insisting a face-to-face meeting for negotiation. The author’s insisted she was unable to speak and wanted to read the contract beforehand. Judd sent the contract “roughly a week later.”

The contract had several clauses the author did not like. First, it stipulated all her work and concepts before and after the contract would be deemed a “work product” and owned by Dangen. Second, Dangen would have the right to copyright all of the author’s “work products”, and grant them royalties if they were ever used forever.

Due to the author’s work on Fight Knight and Devil Engine, she claims this would have given Dangen a “backdoor” into copyrighting “significant” portions of those games. Finally, the contract would have forbid the author from contacting anyone who was published or working with Dangen (after one year of work).

Judd also sent a Slack message, emphasizing that she could not discuss internal issues with developers. The author brought up issues with the contract, including how it seemed to be based on a translator’s contract, the pay, the non-competition clauses, and how she could have to pay damages up to four times what she was paid “at any moment and for any reason entirely at your own discretion.”

Judd stated he felt the contract was standard (written by DDMA’s law firm), but he allowed the author to write her own contract. The author did not work on the contract until after Devil Engine received their royalties.

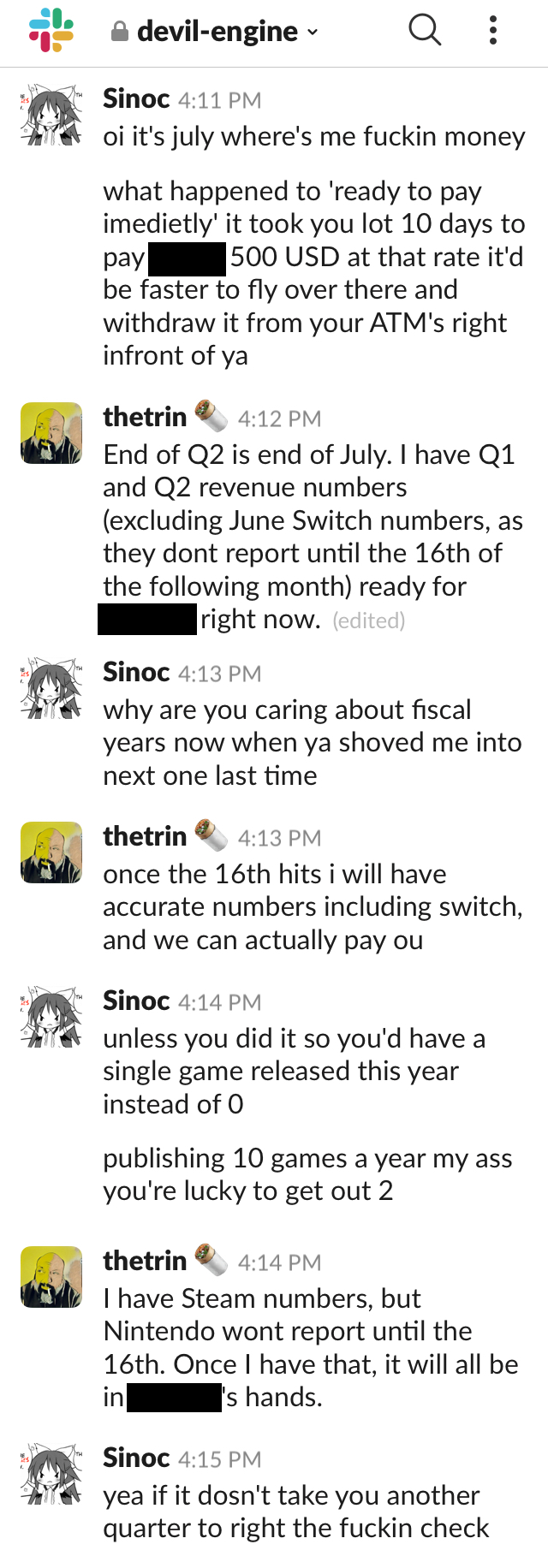

On July 1st, Devil Engine‘s lead developer (Sinoc) took to the staff Slack demanding his royalty money. This was the alleged due date- after Q2 ended (April 1st to June 30th).

Ramachandran claimed that the end of Q2 came at the end of July, and that he was waiting for royalty reports from Nintendo due on the 16th. The lead developer did not believe this.

Ramachandran then asked the author to mediate the situation by discussing Sinoc’s issues and presenting them to him. This led to an agreement that they would wait until July 16th, and invoice Dangen for Q1 and Q2’s royalties.

When the royalty statement came through, the author noticed the launch month sales for the Japan region were absent. When asked, Ramachandran apologized and sent a corrected report within a few minutes. The missing sum was roughly $7,000.

Another issue that arose with an additional 8% tax on business expenses, with unapproved business expenses such as $1000 on Twitter adverts. This resulted in the Devil Engine team paying an additional $80.

To prevent further delay, the invoice was agreed upon. The author then makes a damning claim that “DE and FK never received funding or porting support from Dangen. DE dev created the port for DE’s Switch version without assistance from Dangen staff.”

The author then accuses Dangen of withholding payment again, claiming they did not know how to file or calculate withholding tax for a US developer (the Japanese equivalent being source-based tax).

When the author approached Judd asking why Dangen had never prepared to pay a US developer (especially since considering it had been six months since Devil Engine‘s initial launch date), Judd was evasive, and stated he would get the author in contact with his accountant. This never happened.

For fear of never getting paid, the author “agreed to have Dangen pay 20.42% of our royalties to the Japanese government in withholding tax, so long as Dangen provided me proof of this payment so that I could file for a tax refund.” The proof of payment never came.

The author had to allegedly resort to “breaking up the funds into transactions small enough to not set off Japanese overseas bank transfer restrictions and have slowly dispersed the funds to DE’s team over the past half year.” When the proof of payment’s absence became “widely rumored,” Judd allegedly sent a “poorly made Word document” that still lacked the information needed.

In the post’s summary, the author also claims that the Devil Engine developer has no control over the Steam or Nintendo Switch product pages, and that no royalty payments for Q3, Q4, or any proof they paid Japanese withholding tax.

Later in the post, the author explains that due to most projects involving Dangen also involved a game’s original publisher, that other games have not been affected in the same way.

As Dangen only handle those game’s Japanese localization, they are not involved with calculating revenue share. Other projects purely under Dangen allegedly do not have their royalties due yet.

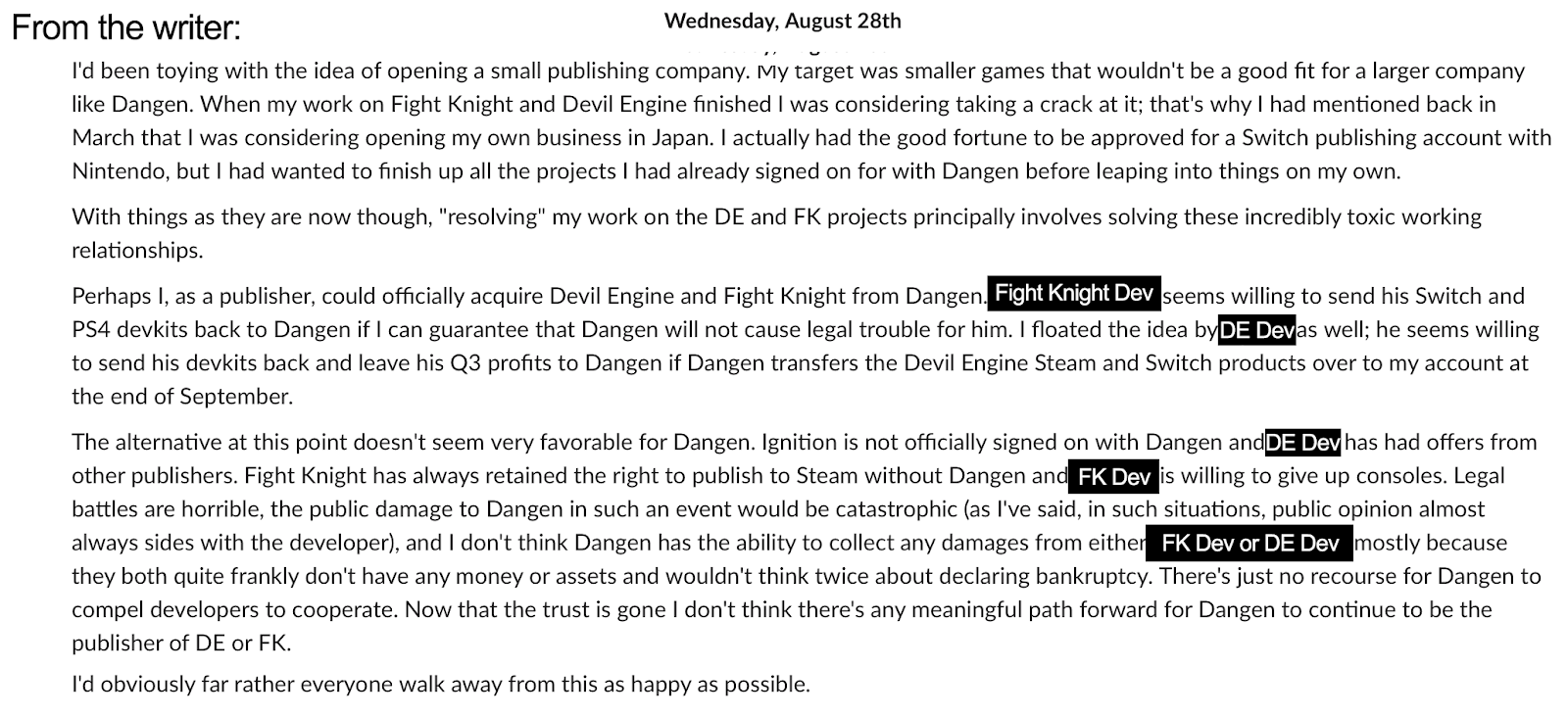

A Fight Knight developer wanted to terminate his contract with Dangen in May, but held off due to Judd’s earlier alleged threats against the Devil Engine team, and waited for them to receive some payment. He terminated his contract on July 24th, 2019.

While the author writes as though it were an individual, later they refer to the developer of Fight Knight as a collective. Nonetheless, the Fight Knight developer officially announced they had terminated their contract with Dangen on October 24th, 2019.

This resulted in Dangen’s law firm sending a threatening letter a week later. It claimed they “had evidence that all of FK dev’s frustrations were “misunderstandings” and that, “rest assured, Dangen is not prepared to relinquish any of its rights to publish and distribute the Game.” It also claimed that the author had lied to the developer, even though that developer was a witness and recipient of the majority of the grievances.

While the letter requested the developer email Judd (and specifically not the law firm) to discuss the matter, allegedly neither he nor Ramachandran “never attempted to e-mail, PM, or otherwise directly contact FK’s lead developer.”

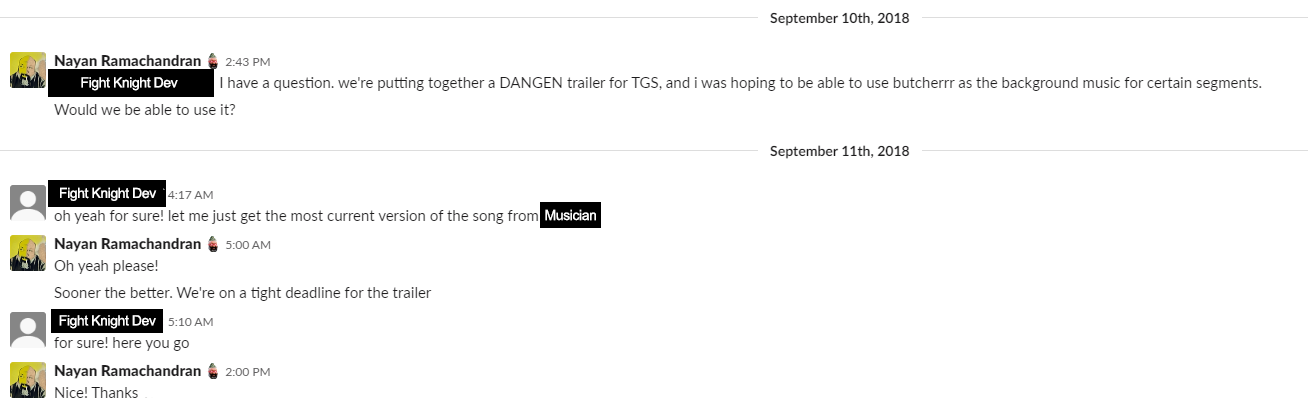

Dangen’s event manager Justin Pfeiffer then allegedly used Devil Engine‘s music (composed by Joseph B) without permission at Bitsummer 2019 (the linked video has since been deleted). The author claims no announcement of the music’s source was ever given, or advertisements for Devil Engine.

Dangent also uploaded the entire game’s soundtrack to their YouTube account, and used one of Fight Knight‘s tracks in an advert for Dangen itself- allegedly without the permission of either developer. The advert came almost three months after the Fight Knight developer had terminated their contract. Further, trailers uploaded to the developers accounts would allegedly be ripped and uploaded to their own account, and titled the “Official Trailer”.

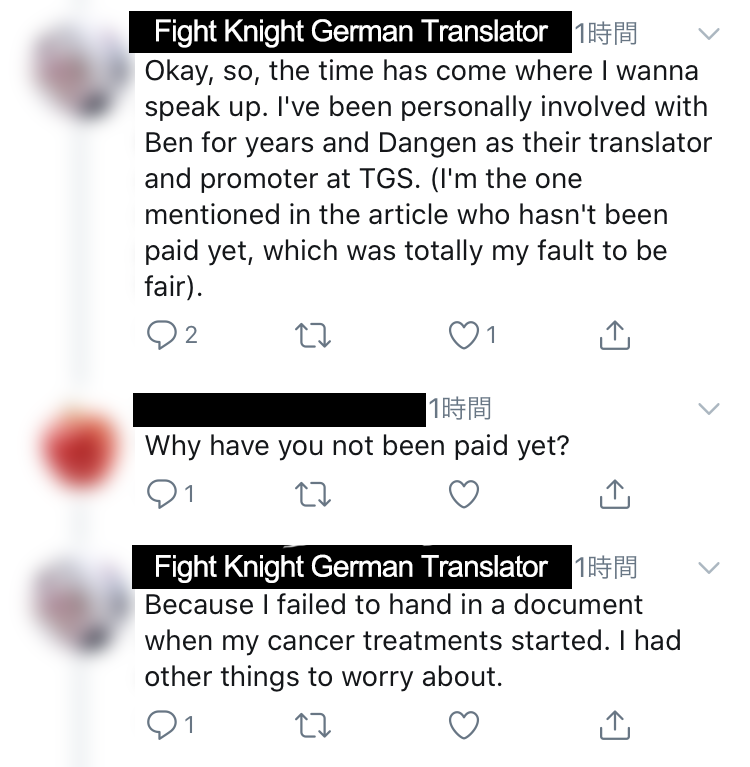

The author then details other collaborators on Devil Engine and Fight Knight who went unpaid or were paid late- including a promotional poster artist, non-Japanese musicians for Devil Engine (who Dangen also demanded sign another unfavorable contract first, or they would keep 20% of what was owed), and translators.

Furthermore, “Pfeiffer attempted to have Dangen musicians sign their rights to their music to him in order to create a Dangen Compilation Album. Dangen musicians were being offered 10% of the sales of this album. This album greatly insulted a majority of the Dangen musicians. At this time, DE dev still had not received any of his money.”

In summation, the author states that Dangen had been late or outright refused to pay royalties, provided no way for creators or collaborators to submit forms for refunds on taxes, attempted to make developers sign unfavorable contracts, acted incompetently on numerous occasions, and used and took control of developer assets without the developer’s permission.

Judd is meanwhile accused of taking advantage of a younger female developer along with other women, becoming hostile once the failings of Dangen staff were brought up, offered the author of the post a job purely based on her gender and race, threatening negative consequences on a developer for the actions of another, and breaking NDAs.

The document’s conclusion alleges that Alex’s tweets had “alerted many Dangen developers to the fact that their games’ profits directly go to one of Ben Judd’s companies. (As far as I can tell, Dangen’s office address is registered to three separate companies in Japan: Digital Development Management Agency, Encapsulated Software, and Dangen Entertainment. This is publicly available information I repeat here in the public interest.)”

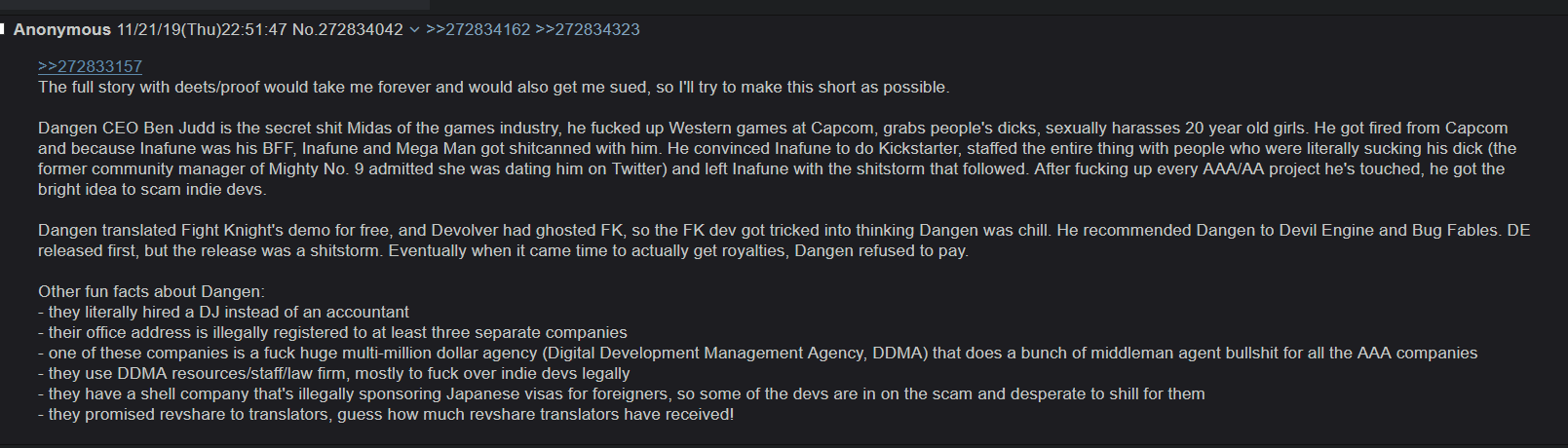

Once the story became more prevalent on social media, some individuals [1, 2] found a screencap from an unknown message board made eight days prior to the medium post.

The message board post makes several of the same accusations as the Medium post (that Judd had been predatory to a 20 year old woman, that Dangen refused to pay royalties, and Dangen’s offices being registered at three separate addresses).

The allegations of Judd hiring staff for Mighty No.9 may have some credibility, as Digital Development Management were involved in assisting the project. Judd may also be a former Capcom employee, with Dangen formed of former employees from Capcom, Grasshopper Manufacture, Q-Games and Playism.

Dangen Entertainment Response

Following all of these allegations, Dangen produced their own Medium post (specifically “written in parts by different members of Dangen”), refuting the claims. “As THE WRITER and their accomplices have attacked so many of us, directly and indirectly – not only Dangen but (as we’ll show) also our clients and their games – it only felt right to respond as a group.” The post refers to the author as “the writer”.

The post begins claiming that the emails and private message snippets are “intentionally misleading snippets” that the author was “twisting them, cutting key facts out or even sometimes inventing new ones in a clear attempt to discredit and embarrass, and all in order to hurt you and your business, especially when, as we will show, THE WRITER themselves is set to directly benefit from it both professionally and financially.”

The author’s own medium post stated in its introduction that their “intention is neither to profit personally nor to particularly seek financial harm against Dangen Entertainment, Ben Judd, or any other persons incidentally mentioned. I do not seek to financially harm game projects currently published by Dangen Entertainment. Any games, developers, or people mentioned are only mentioned in the interest of providing the complete and true story to the public so that the public may be warned.”

Dangen’s post continues, “THE WRITER not only omitted this fact from their piece, but claimed that there was no financial interest attached to their story. We have proof that THE WRITER has much to gain from destroying our reputation.”

The post further claims that the “inappropriate things” dating back to 2013 was “when most of us weren’t in the industry and Dangen wasn’t a company yet. We’ve seen mistranslations about the original article and people with ulterior motives use this to their benefit.”

At least two sources claim Dangen was formed in 2017 [1, 2], however no accusation in the original post mentions the year 2013. The only possible one could be Alex and Judd’s relationship (the estimate of 2014 having some leeway), and Judd still may have had some “clout” to allegedly take advantage of another.

First, Dangen’s post alleges that the writer seeks to become a publisher and intended to profit from the Medium post, based off an earlier Slack message allegedly from the writer.

If true, the post does indeed show the author did desire to make their own publishing house. While the decision to do so in Japan as oppose to the US is debatable (as Japan’s property prices can be quite high, and it would be logically cheaper and easier to set up a business in the country you live in), her alleged post indicates that a legal battle between developers who wished to leave Dangen would cause public damage. Whether making the grievances public knowledge would help that case is debatable.

The topic of “The Developer-Publisher Relationship” is rather brief and does not address what the author accused them of directly. While Dangen admits “occasionally mistakes and human errors are made“, they “strive to have strong, friendly and successful relationships with our developer partners.”

“Game development and publishing are complex, as are the relationships between developer and publisher. Both parties must work in good faith to coordinate a great deal of information and activities. As with any business, occasionally mistakes and human errors are made. They can be anything from a missed approval to delayed game development. We strive to have strong, friendly and successful relationships with our developer partners, in the hopes of finding real success for their games. When a challenge presents itself, Dangen’s goal is always to find a mutually agreeable solution and a better way forward.”

Focus then shifts to the accusation that Stern lied in the GameIndustry.biz interview. They claim that services such as localization, porting, and developer support are recouped first to be spent on preparation for release. “In other words, Dangen pays their back-end percentage worth of revenue to cover the localizing, porting, and dev support BEFORE any money is recouped. The developer is NOT invoiced or financially obligated to repay this money themselves.”

The example used states that when Dangen invests $10,000 to localize and port a game in development, and the game’s sales generate $50,000 after taxes and platform fees, that “the recoupable expenses are deducted first and NOT from the developer’s share. $10,000 is deducted from total net revenue, leaving $40,000 to be shared. The amount of revenue Dangen will earn has been reduced in proportion to the revenue share because it affects both parties.” Dangen again reiterates this is the industry standard whether you are an indie or a AAA publisher.”

The post then discusses “Dangen’s Track Record”, stating what the publisher did for both Devil Engine and Fight Knight, including articles on news websites, showing the game at conventions and events, secured content creators to create videos about the games, providing Nintendo Switch development kits (“at a time when they were very difficult to secure”), and that both games sold at least 1,500 units.

“Continuing, the post then outright refutes the author’s claim about the missing and delayed payments.

Dangen refutes any implication of robbing developers. Dangen has paid over 30 different outsourcers, 15 different developers over multiple SKUs, and, as per contract, has submitted sales reports that allow for invoicing. Certain payments have yet to be completed due to non-standard payment requests, but Dangen has been in constant contact with the developers and is working to fulfill each request. Our bank records show that the Devil Engine developer who was making the false claims has, in fact, been paid. Additionally, they have been sent the latest Q3 sales report as per the standard contractually agreed to timeline.”

Dangen then addresses several “claims of specific non-payments” to other collaborators, and ascertains each was paid on specific dates (including the poster artist). Regarding the non-Japanese musicians who lost 20% of their payment, Dangen claims that a contract was in place (and needed to file for withholding tax relief) and that the author had advised against the artists not to engage with the contract.

A musician who worked on Devil Engine (who the author claims was “pressured” into signing another contract, and the author paid them out of her own funds), had allegedly not been pressured to sign a contract, and that “a one time contract” for a legal paper trail was recommended by him.

They also claim Dangen had paid the withholding tax for the musician. The author and Devil Engine developer allegedly “stepped in and said that they would be paying the composer instead, and we complied.” In addition, they state “all musicians related to the Devil Engine Ignition arrangements have been paid for their work.”

Regarding Fight Knight‘s German translator not being paid, Dangen claims that paying some outsourced work can take “as long as a quarter” and that it is an industry standard. They also claim that the translator had been unable to submit the appropriate paperwork to be paid, further delaying the process.

Dangen does admit to one mistake – missing the Golden Week Sale opportunity. An alleged message from Judd to the author states he paid 600,000 yen in compensation for the missed sale. They also claim the author did not focus on how Dangen resolved the issue (though the author did mention it).

“This is 100% a mistake that Dangen accepts. It was a sale that we were not prepared for, and the Devil Engine team was rightfully upset at us missing it. In response, Dangen respectfully agreed to pay the equivalent of the expected sales lost from missing the Golden Week Sale, hoping that it would show we would own our mistakes. This is absolutely not industry standard, but a display of our good faith and a desire to correct our errors.”

[…] Note that THE WRITER does not focus on how Dangen dealt with this mistake in their article, but rather focuses on destroying Dangen’s reputation for their own benefit. Currently, Dangen has improved the sales planning process and any of our current developers can attest to us never missing any other sale since.

Later, Dangen also admit to it being their mistake that the Fight Knight developer spent their own money on a lawyer which was then unneeded due to the original contract being lost. “This is absolutely a mistake on Dangen’s part. We were in discussions to cover this loss when the developer went dark, preventing us from continuing this conversation.”

Dangen also claim that the Devil Engine music used at Bitsummer 2019 was used with permission. “On the day in question, Justin Pfeiffer verbally made THE WRITER, the DE representative in attendance at BitSummit 2019, aware that he had intentions to include one song from Devil Engine in his BitSummit pre-party DJ set and was granted verbal permission, “You have my approval,” from THE WRITER.” They also claim the author asked to record the event to show other developers of the game, and that the music was intended to promote the game.

The Devil Engine soundtrack being uploaded to Dangen Entertainment’s YouTube channel was allegedly done when “a non-affiliated third party had uploaded the entire soundtrack to YouTube of their own accord. The purpose was to direct YouTube viewers to an official channel that included the Devil Engine Original Soundtrack store page at the top of the description for legitimate, promotional purposes.”

This was also allegedly to help increase sales of the soundtrack, and the author’s Medium post was the first time they became aware of the developer’s wishes. While they claim “Dangen has since removed the videos,” at this time of writing, the videos are still available (archived here) on their YouTube channel, with the video’s description linking to the soundtrack on Steam.

Nonetheless, Dangen also insists they had received permission to use a Fight Knight song in their company trailer. They also claim that the contract between them and the Fight Knight developers has not been “legally terminated,” and that no one on the Fight Knight team had not “expressed that the song should not be used in the trailers.” Dangen stated they ceased the use of the song in the trailer, and as of this time the video is no longer available. No mention was made of the money from Bandcamp.

Dangen also shared information the allegedly “last-minute” request for a developer video for Kinda Funny Games’ event. They claim Ramachandran “suggested not only that either team member could take on this task, but that we only ask that they do it if they can.” While the included alleged Slack message claims the video could have been done “in the morning”, neither the image of the alleged Slack message or the email make the matter sound any less urgent. Although they do claim they sent the video, Kinda Funny never used it.

Discussing the accusations of “Mismanaged and Unapproved Marketing to Nintendo”, Dangen claim the author’s claims are “completely inaccurate. Due to the sensitive and private nature of Nintendo of Japan’s procedures and policies we cannot discuss this in detail, but we maintain that we did pursue this opportunity to the best of our abilities. In the end, as is the case with first party processes, the timeline and final decisions were completely out of Dangen’s control.”

Dangen yet again claim this is standard practice for first-party processes, that it is the developer who chooses whether they “spend the time to create assets for first party evaluation,” and that there is no guarantee any evaluations can result in an opportunity. While Dangen state “All of this was clearly conveyed to the developer,” they did not answer or confirm if they pursued an opportunity with Nintendo without the Fight Knight developer’s knowledge, or if the developer had control over what opportunities Dangen pursued.

Moving onto Devil Engine‘s “troubled release,” Dangen claims the developers received notification of the Nintendo Switch product code on November 12th, and Dangen designated three months for the process of creating the other version even while the Windows PC version was “sitting and waiting” for a simultaneous release.

The third-party issues the author briefly touched upon allegedly had key information omitted, according to Dangen.

“Initially, we asked the developer not to sign this particular third party agreement without allowing us to look it over. Dangen offered to take care of the interaction with the third party and sign the paperwork to protect the developer from any legal ramifications. Shortly after, Dangen received a sample contract from the third party, and felt like many of the terms were unfair to the developer. Dangen asked the developer to hold off on signing until Dangen suggested possible amendments of the contract to the third party. During this time, the developer signed the agreement with the third party without giving Dangen notice. Dangen only found out about this through THE WRITER — the Devil Engine developer never notified Dangen of this development. As a result, the Devil Engine developer ended up signing a contract that caused them several problems.”

It is entirely possible that if the author’s version of events are true, then the developers may have rejected even genuinely useful advice from Dangen. The third party allegedly created music for Devil Engine that the team did not endorse despite contractual obligations. The third party also allegedly “created assets” without permission of the developers. Dangen allegedly spent 350,000 yen for legal advice, and while they initially agreed to cover 150,000 of that cost, would allegedly cover all legal costs and not charge the developers for it.

Dangen claim “The developer recognized this and seemed to appreciate the gesture, as evidenced by the following screenshot,” but then use a screenshot between Judd and the author (where Judd clams the developer was happy with his decision).

Dangen further claims they worked in developers favors, describing an alleged scenario where they worked to plan marketing, press releases, and “securing musical talent” for Devil Ignition DLC. They claim the author was to work on this DLC, and that either her or the development team suddenly canceled the DLC.

While the cancelled DLC may have been a result of the developers walking away from the publisher, it is unlikely the author would have had time to perform the alleged duties she took from Ramachandran across Devil Engine and Fight Knight, and create more DLC. Though this does depend on the nature of the supposed DLC.

Dangen also defend that their streams support their developers, rather than just themselves. Dangen link to six moments from Twitch [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], and their own official YouTube and Twitch channels at this time of writing show any partying or drinking.

When Judd allegedly paid the Fight Knight developer’s legal fees, and compensation for the lost Golden Week sale, Dangen claims they offered to pay the author the equivalent of part-time work to help “mend the relationship” between all parties. Whether the author accepted this is not elaborated upon, but they claim that “despite this, THE WRITER constantly mentioned they were doing “everyone’s jobs” and deserved more money, even suggesting that they should get a direct revenue share to cover the work they were doing.”

Later in the post, Dangen claim the author (acting as a representative of Fight Knight, Devil Engine, and an unnamed third project) began to make demands for more pay (beyond a proposed compensatory fee akin to part-time work), attempting to gain control over the projects, and gain a bigger share of revenue. “This became a trigger to withholding tax issues that delayed payment to the Devil Engine developers and further damaged the relationship,” Dangen claim, “This was 100% a request from THE WRITER, not from Dangen.”

Going further, Dangen claim the author had the majority of communications to the developers funneled through her. “Dangen had to believe that everything THE WRITER said was true.” This eventually resulted in no direct contact with the Fight Knight developers for “nearly six weeks before they suddenly posted a message listing their frustrations, left Slack and closed down communications.” They claim they have attempted to reach out to the developer, but have received no replies.

When discussing the Fight Knight developer’s desire to terminate the contract, Dangen claims they never sent any threats, and reaffirm that the contract had not been “legally terminated,” as mentioned prior.

“There was a one-sided slack message that came from the developer on July 23rd. This does not constitute a legal separation as per the contract. Furthermore, Dangen did make an approach to the developer via their counsel to go over some of the misunderstandings that the developer was under. Context was provided and explanations were made, but the developer never sent any response.”

No screencap was included to reinforce this claim.

Regarding the alleged contract the author was offered, Dangen claim the author “uses hyperbole and completely misinterprets the terms of the contract.” While Dangen claim the contract would not have given them control over all of her work product, they do not provide their own copy of the contract.

Dangen also claim they participate in “a standard contract process,” allowing both parties to send copies of the contract back and forth with adjustments, suggestions, and negotiation on terms. They also claim the author contradicted herself, however Judd’s alleged offer to allow the author to writer her own contract came after the initial contract was rejected. Dangen claim that they had “full expectation that [the author] would negotiate the terms they felt were fair for them” in the first place, without being prompted.

When discussing the author’s claim that Ramachandran would not receive royalty reports from Nintendo until July 16th, 2019, Dangen claim it is “another clear example of THE WRITER admitting that they do not know if something is true or not, yet still trying to use it as ammo to further ruin Dangen’s reputation.” The Author had stated they did not trust Ramachandran’s word due to past alleged incidents.

Nonetheless, they claim “first parties such as Nintendo close their books at different times. This can totally be fact-checked and should be.” According to Nintendo’s Investor Relations website, Nintendo’s annual reports for the fiscal year end on March 31st. We also see in the 2019 report that the fiscal months are divided up into three month periods. As such, Q1 would last from April to June, Q2 from July to September, and so on. July 16th, 2019 would have been at the start of Q2 2020.

However we cannot confirm when Nintendo hands out royalty reports, and it seems unlikely they would do so on a yearly basis. It may be possible Dangen was awaiting for Q1 results- ending June 31st, and compiled and sent a few weeks later on July 16th. Devil Engine released on Nintendo Switch on February 21st [1, 2]. The game was also released on Windows PC (via Steam) on the same date.

The author claims the Devil Engine developers were expecting their royalties “on July 1st, 2019, after Q2 (April 1st to June 30th) ended. This would include our Q1 (January 1st to March 31st) sales as well.” This would put the game’s launch at Q4 Fiscal Year 2018 (January, February, and March 2019). Yet there has been no claim of royalty reports or royalties being due in Q1 2019 (April, May, June), and instead Q2 2019 (July, August, September- particularly July 1st).

This creates more questions. Why would it take Nintendo or Dangen over three months to create a royalty report if Nintendo’s financial quarter ended just over five weeks later? If there was to be a delay due to Nintendo having finished the report, why only a delay of a few weeks rather than another quarter? If Dangen knew the Nintendo royalty report would come later than other platforms from prior dealings, had they offered the Devil Engine developer a chance to receive part of their royalties earlier (such as Windows PC sales)?

Even if Nintendo offer royalty reports on a more frequent basis, it creates more problems. The delay from July 1st to July 16th is just over two weeks. Assuming this means Nintendo can produce a royalty reports on a bi-monthly basis (every two weeks) why were there no Nintendo royalty reports generated from February 21st (the release date) to July 1st- a period of just over 18 weeks? Without knowing more about Nintendo or Dangen’s royalty report writing process, it is difficult to ascertain the truth.

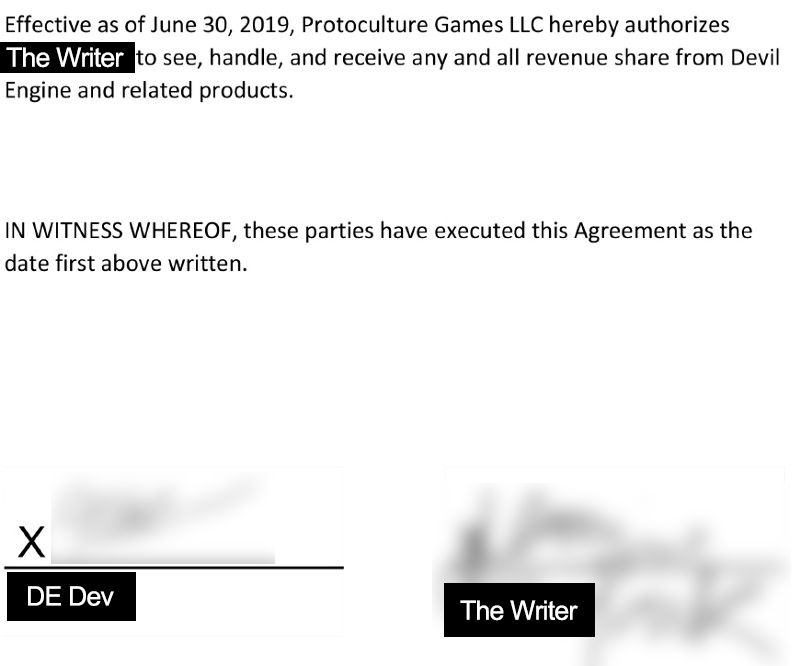

Irregardless, Dangen claim the author had requested to handle all of Devil Engine‘s tax paper work as a proxy, and “see, handle, and receive any and all revenue share from Devil Engine and related products.” This was agreed upon in an alleged contract, which Dangen included a snippet of below (though no mention of tax paper work is included):

Later Dangen seem to make the shocking implication that the author intercepted the money meant for the Devil Engine developer, that Dangen allegedly did send.

“Much of the vitriol from the Devil Engine developer and THE WRITER stem from not being paid, but many of these delays stem from the mistaken assumptions of THE WRITER, who was properly paid. Once the money had left our bank account, we were not responsible for the delivery of the money from THE WRITER (proxy) to the developer, especially since the developer insisted that a proxy was the only payment method they would accept.”

While Dangen make frequent claims that the author was attempting to gain a larger share of revenue from the projects they worked on, the above contract seems to have given them permission to- with the developer granting “any and all revenue share from Devil Engine and related products.” This point is never brought to attention in Dangen’s own Medium post.

On the subject of the withholding tax, Dangen claim the author “constantly misunderstood Japanese laws regarding withholding tax. For example, THE WRITER made the incorrect assertion that they would not need to pay withholding tax as a resident in Japan, illustrated in the screenshot below.” The author allegedly claims in these messages that withholding tax is unnecessary.

Dangen also claim the websites the author linked to [1, 2] actually reaffirm that withholding tax need to be paid, and they instead wait for their own Japanese accountant’s word on how to proceed.

In the author’s original post, they make no such claim that the withholding tax was unnecessary. She claimed Dangen “didn’t know exactly how to file or calculate withholding tax for a US-based developer,” and that not being prepared to pay a US-based developer with at least six-months notice was unprofessional.

Regarding the two websites the author linked, the first does state on page 5 that a “Non-resident (an individual other than a resident) or a foreign corporation (a legal person other than a domestic corporation)” would be subject to the withholding tax, including for:

“(8) Royalties for any industrial property right or copyright, consideration for the transfer thereof, or royalties for machinery, equipment, etc. pertaining to domestic operations from a person doing operations in Japan;

(9) Any amount sourced from work in Japan among remuneration paid for the provision of personal services including salary, etc., certain amounts of public pensions, etc., and any retirement allowances, etc. sourced from work performed while the beneficiary was a resident (non-residents only);”

As the author said in their own medium post however, “Under Article 14 of the US-Japan tax treaty, royalties from Japan sent to the US should not be taxed more than 10% by Japan.” The form however would seem unnecessary, as the developer was not operating in Japan as a “foreign resident.”

Dangen also claim that they “can attest, however, that since our tax attorney was Japanese, it did cause for slower withholding tax communication as far as international accounts were concerned. This has now been rectified with our new international tax attorney.”

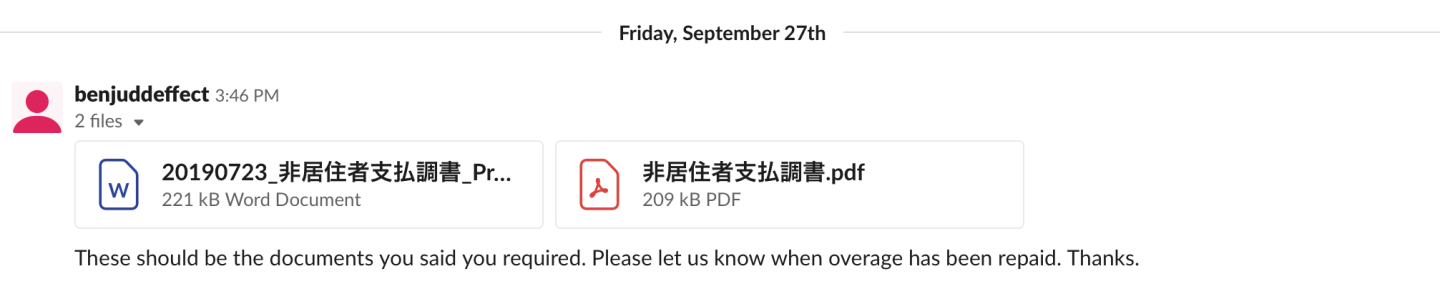

Dangen explained the author’s claim of them refusing to provide a proof of payment was due to a miscommunication. “The WRITER initially asked for a 源泉徴収票. (certificate of withholding tax) […] The WRITER later mentions they need a “proof of withholding.” […] Once it became clear that THE WRITER wanted a proof of payment (支払調書) and not a proof of withholding, Dangen did send one to THE WRITER.”

Dangen further claim that the 源泉徴収票 (certificates of withholding tax) are only to be provided to salaried employees. They also claim “according to Japanese law, withholding tax must be deducted from each payment made to an external party. The withholding tax is NOT paid separately by the company.”

Dangen further claim that due to the proxy payment, they not only overpaid due to a unique category of withholding tax, but that “after Dangen requested that THE WRITER pay the overage back so that accounting records could be corrected, THE WRITER ceased contact. This was the last official communication Dangen had from THE WRITER until they wrote their article.”

Dangen then attempts to dissuade accusations of not working during certain periods of time. This was via a screenshot of an alleged email from Ramachandran on May 2nd as proof Dangen were working during Golden Week 2019, and the claim that the company’s anniversary live-stream was pre-recorded.

The alleged screenshot from Ramachandran stating “we’re all off until Tuesday” from the author’s document raises questions on which is legitimate. The author’s own screenshot did not show a date.

The medium post then delves into the author’s alleged ulterior motives, elaborating on their earlier claim that the author desired to be a publisher. They included screenshots of an alleged email from the writer that stated they wished to acquire Dangen titles, while “casually threatening that catastrophic public damage might ensue.” They claim the latter has come to pass with the accusations the author has publicly levied at Dangen.

Dangen’s medium post then moves onto the alleged “toxic” abusive and hurtful messages they received from Devil Engine and Fight Knight developers- even including screenshots alleging they were abusive to other game developers under Dangen.

Dangen also claim “multiple posts popped up on Twitter, Steam, Reddit, 4chan and Resetera” from alleged Devil Engine developers, claiming that the developers of the unknown third game the author had acted as a proxy for (judging by two of the alleged screenshots Bug Fable) had not been paid for their work and no profits would go to them. Attempting to search for both of the alleged tweets below showed no results.

This allegedly took place shortly after the “unknown” third developer “cited an end of contract with THE WRITER, therefore THE WRITER was removed from the Slack channel. THE WRITER had attempted to pull this developer over to their label as well, but this third developer decided to stay and continue to release with us.” Shortly after the alleged slanderous messages, they claim the author’s Medium article was posted.

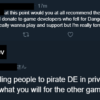

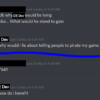

Dangen additionally claim “the Devil Engine developer continued to plan further attacks on a separate Discord. They also reached out to other Dangen-associated developers in order to try and pull them away from Dangen.” Screenshots of the alleged Discord server (along with allegations of encouraigng piracy of Dangen titles and spread defamatory information) can be found below:

Finally, Dangen addressed the accusations against Judd’s behavior.

“Ben Judd has nothing but a professional relationship with the writer, and any accusation otherwise is false. THE WRITER begins the Medium article by linking a tweet that accuses Ben of being a predator. This tweet was made by an ex-partner of Judd’s whom he dated in a mutually consenting relationship 6 years ago. It has nothing to do with the relationship between Ben Judd and THE WRITER, yet THE WRITER pastes it at the beginning of the article in order to try and color the reader’s image of Ben Judd from the start.”

Further, they claim the meeting at the night-club instead took place at a gaming event that had a DJ, and that the conversation remained professional.

When discussing the unwanted private messages and broken NDAs, Dangen claim “There hasn’t been a single time in the several months of back and forth communication where this was ever suggested, requested, or even vaguely hinted at. This was merely normal business communication that occurred when business discussions were necessary.” They also re-iterate Judd’s flexibility whenever the author had to cancel appointments.

Further, Dangen claim Judd made no demand for the writer to attend Bitsummer 2019, and that (as shown in the alleged screenshot below) the author was happy to go once Judd covered the travel costs.

The allegedly forced meeting to see the author face-to-face was also explained as being out-of-context. “The truth is that a face-to-face meeting with a potential contractor was suggested. In fact, Ben even suggests waiting a few days due to THE WRITER’s lost voice. Ben thought that meeting in person would be a more efficient way to hash out the basics of the discussed contract before spending legal money to create the final contract.”

They also claim the author further “embellished the truth” as the meeting at the cafe far-away from Dangen’s headquarters was in-fact “a mile from Seattle’s Best, which is a two-minute walk from Dangen’s Yodoyabashi office — hardly “far” by any stretch of the word.” While we have been unable to find the address of Dangen’s Yodoyabashi office, there are seveal coffee shops in Yodoyabashi called “Seattle’s Best Coffee” (possibly a chain). While we were unable to find a Sumitomo Building, we did find Sumitomo Corporation in Yodoyabashi.

Judd then took to writing the final segment of the Dangen Medium post, addressing Alex’s accusations against him. He stated all claims were false, and phrased his statement as though Alex initially made the accusation he was “a racist, misogynist, and sexual predator” without provocation. Judd claims the relationship with Alex was always consensual, and at networking events only ever had relations with Alex, his ex-partner.

Judd further claims that both the author and Alex were “at one point were the victim of a horrendous public shaming and online harassment campaign while I was dating them. I don’t understand how they could have gone through that kind of pain and wish it on another person.” Judd also ascertains that “several key individuals who spent a great deal of time with my ex-partner” would be able to vouch for how “complicated” his relationship with Alex was.

He has offered to have these individuals meet “any developer who may have concerns or members of the press who are willing to cover both sides of this story,” as long as they remain anonymous.

Summary and Closing Thoughts

In summary, Dangen Entertainment only confess to using missing the Golden Week Sale opportunity, and that the Fight Knight developer had wasted money on a lawyer to look over a contract that would end up lost (which Dangen then reimbursed them for). They also claim they have now hired an international tax attorney, to help expedite the withholding tax process.

However, every other accusation was refuted with claims that individuals had consented, that the author had talked individuals out of contracts the individuals themselves had initially requested, that Dangen acted in industry standard practices, that payments had been sent, and that the author otherwise lied. Judd also denies all accusations made against his character.

Their medium post also made a comment seeming to imply that the delays in Fight Knight were purely from the developer, which Dangen honored and adjusted release dates for. In addition, they claim Japanese withholding tax is not paid separately by the company. While the intricacies of Japanese tax law requires further research, it seems to be true.

The author’s accusations that the Dangen Entertainment team’s streams focused on promoting themselves and partying cannot be proven, as both their official YouTube and Twitch pages show no such videos. In addition there are conflicting screenshots proving and disproving Dangen were working (or not) during Golden Week.

The soundtrack for Devil Engine is still available on Dangen’s official YouTube channel, despite them claiming they would delete them (though other offending videos allegedly using Fight Knight music without permission were). They never directly addressed if the Fight Knight developers had control over what platform opportunities Dangen pursued, or the alleged money owed from Bandcamp.

Claims Ramachandran was unable to provide a royalty report for Devil Engine due to waiting for financial data from Nintendo also brings up many issues. Based on how Nintendo divide up their financial year and hypothesizing how long it would take them to make a report (bi-monthly, monthly, or even weekly), it should not have resulted in a two week delay outside of human error from Dangen or Nintendo. Dangen did not attempt to refute that Ramachandran did not request a delay of two weeks.

Dangen even add additional claims, stating that the Fight Knight developers never provided a legally binding means of terminating their contract, and that the author had attempted to gain more control over and revenue from the projects they were involved with. They also claim the author’s public Medium post was part of a scheme to discredit them and eventually obtain the rights to Devil Engine, Fight Knight, and other games contracted with them.

In addition, they claim the author misinterpreted her contract to work at Dangen (specifically the terms of ownership over her past and future “work product”), and that they expected her to negotiate the terms of the contract anyway (rather than accept the first contract offered).

Strangely, Dangen include a snippet of what appears to be a contract between the author and Protoculture Games, granting the author full rights to “any and all revenue share from Devil Engine and related products”- yet do not focus on this point to reinforce their claim the author was attempting to gain more revenue share. Instead, it was to prove she had permission to access Protoulture Games’ tax related paper-work (though no such claim was in the snippet included).

Dangen also claim that they had sent money to the Devil Engine developer, sent to the author as a proxy (as the developer requested). Dangen may be implying that the author had taken the money without the consent of the developer, or both the developer and author are lying about having received the money.

Finally, they claim both Devil Engine developer and the author were unreasonably hostile and abusive to Dangen staff and other developers, made slanderous claims that other developers were not being paid for their work, and orchestrated further slander and sabotage.

Due to the nature of many of these accusations, it may be impossible to ever truly find out what occurred, as both sides have presented evidence that has disproven the other (assuming it is genuine), or clashed head-on with no clear sign of which was true.

What do you think? Sound off in the comments below!